Ruth Ellen Church with a group of young cooks. Courtesy of Charles Church

The Library Acquires the Archive of Ruth Ellen Church, Longtime Food and Wine Writer and Critic at The Chicago Tribune

The UC Davis Library is proud to announce the acquisition of the papers of Ruth Ellen Church, a food editor, cooking editor, and food and wine columnist for the Chicago Tribune for 38 years. In addition to her work for the newspaper, Church wrote five books, including Mary Meade’s Kitchen Companion: The Indispensable Guide for the Modern Cook (1955), The American Guide to Wines (1963), The Burger Cookbook (1967), Mary Meade’s Sausage Cookbook (1967), and Entertaining With Wine: A Cookbook for Wine Lovers (1976).

Church’s archive contains a comprehensive collection of her food and wine writing for the Chicago Tribune, cookbooks, photographs, résumés and other biographical information, and correspondence with foreign politicians and diplomats.

The first major wine column, by a woman, leads the way for newspaper wine writers

Born in Humboldt, Iowa, in 1909, Church graduated from the University of Iowa with a degree in home economics journalism in 1933, the same year Prohibition ended. She landed her first job with a small Iowa daily, as a society editor, but left shortly after in defiance of the paper’s expectation that she participate in advertising, which would have conflicted with her objectivity as a journalist.

In 1936, she began working for the Chicago Tribune as the paper’s food columnist, writing under the column’s regular byline, Mary Meade. She remained in this position, writing through wartime austerity and into the flush decades that followed, shaping the development of The Tribune’s test kitchen and directing all food photography, until she was abruptly promoted to a position as the paper’s first wine columnist in 1962.

As her son Charles Church recounts, “The Sunday Editor came into her crowded workspace on the fourth floor of the Tribune Tower overlooking Michigan Avenue to tell her a new wine writer’s job had just been added to her duties — she was now to be the food and wine editor.”

Up to that point, Church had been a martini drinker, but she undertook a study of wine and approached her new column with the same acumen she had relied on as a food writer, frequently noting food pairings for the wines she covered.

Church and others like her, writing newspaper food and wine columns in the decades immediately following the repeal of Prohibition, became the guides for a drinking public largely ignorant about wine. These writers in turn learned about wine through organized tastings and dinners, independent exploration, and from writers like Frank Schoonmaker and Harold J. Grossman (Grossman’s Guide to Wines, Spirits, and Beers), as well as from literature produced by winemakers and wineries, such as the Paul Masson winery’s booklets Ways with Wines and Ways with Brandy. Church often included reviews of her sources at the end of her articles.

Reporting on American wines

Church wrote prolifically. She covered beverages other than wine, such as Scotch and beer. She wrote about brandy and vermouth. She wrote about Mexican wines in 1965 and about pairing California wines with Mexican food.

“California wines which most of us thought would be fine companions for Mexican delicacies included Paul Masson Gamay Beaujolais and Emerald Riesling, Wente Bros. Livermore rosé, and three reds from Louis Martini: Mountain Zinfandel, Mountain Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Sauvignon.”

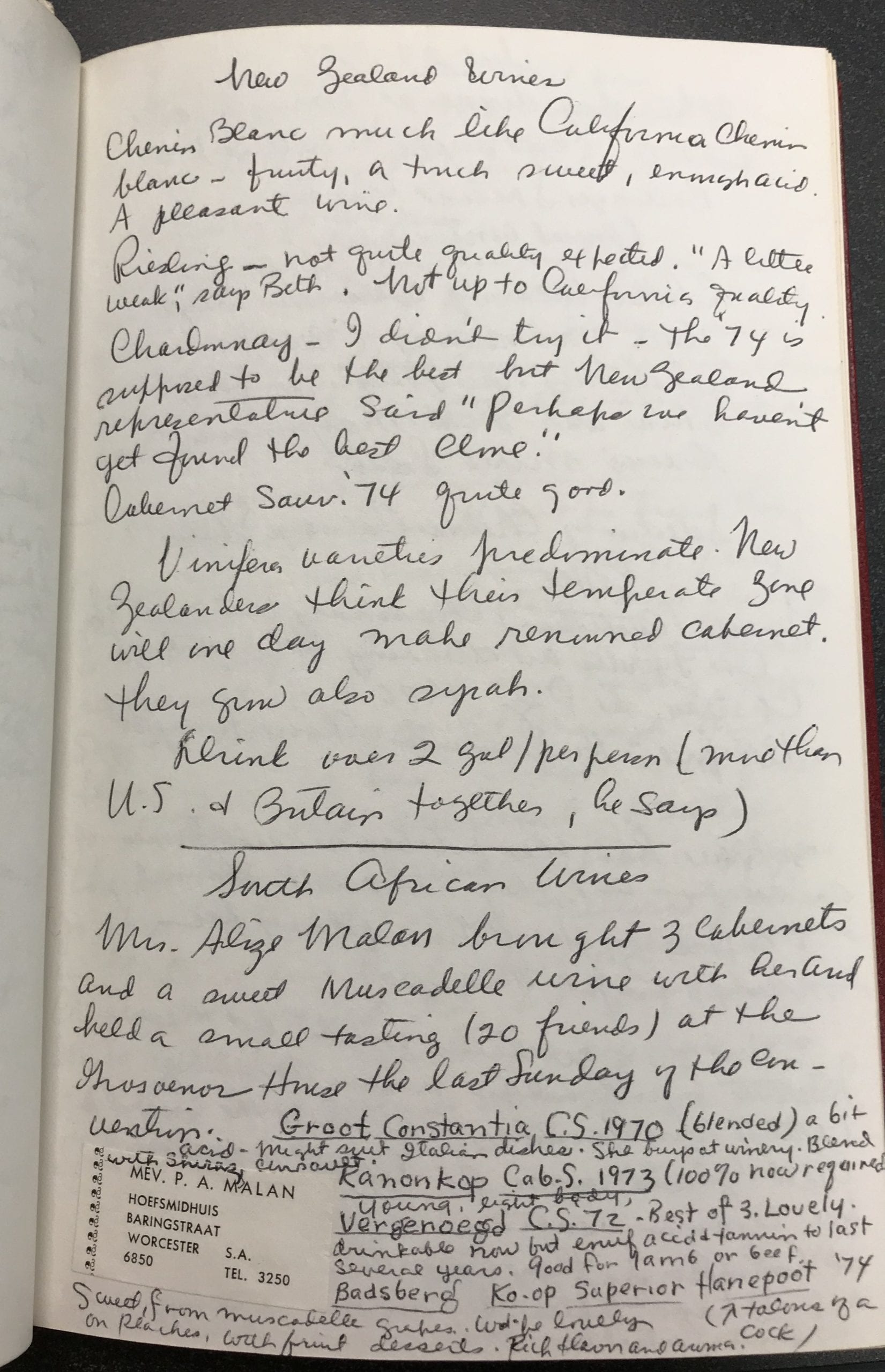

She visited vineyards all over the world; among her papers are journals that document her travels to wine regions in Greece, Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden, and England.

She also returned often to California, where she befriended Maynard Amerine, a professor in the Viticulture and Enology Department at UC Davis. She continued to write about the university into the 1960s, when she covered the arrival of a smart, experimental professor, Ann Noble, who eventually created the wine aroma wheel.

And she wrote about California wines as they were coming into their own. In a 1966 article, she noted that California wines had developed a European market and were now being shipped to Paris. She included a list of the wineries, noting:

“I have been pressured a bit by some of you men readers who would like to know the names of the wines sanctioned by the state department for use at diplomatic functions. Chosen by a committee of six wine experts, they are all wines of which we may be proud. But they are by no means the ONLY outstanding American wines.”

The list included many wines from Almaden Vineyards, several wines from BV, Buena Vista Vineyards, The Christian Brothers, Stony Hill, Wente, and Souverain Cellars, among others.

“Do Wines Make Women Giggle?”

An interesting effect of the sudden change in the trajectory of Church’s beat was that her regular audience changed suddenly from one dominated by women, drawn to the recipes and culinary wisdom of Mary Meade, to an audience that would have included as many men. Her training and practice as a journalist prepared her for this transition, but it’s clear she was affected by some of the comments that her new male audience members, sources, and dinner companions made about women, and she made a point of writing about and to women consumers and winemakers, and correcting misrepresentations of women and alcohol. Usually she did this with an admirable sense of humor and diplomacy, a mark of 1950s-era women that I’ve grown to respect, but there was one piece that I came across early as I was looking through her archive that I couldn’t shake. It’s from a column titled, “Do Wines Make Women Giggle?” She opens with this:

“’Women don’t know how to drink wine. They take too much and get giggly.” So said a member of several gastronomical societies in explaining why so few wining and dining groups open membership to women.

This is simply not true and the more I think about it the more I wish I had told this man so instead of murmuring a polite, ‘You really don’t believe this, do you?’”

She went on to describe a splendid wine dinner hosted by the ladies of Confrerie de la Chaine des Rotisseurs that included fine wines like Mercier Reserve de l’empereur, brut, 1959. The piece was conversational, erudite, written for the people, and filled with delight — a perfect example of Church’s art at its best.