Julie McIntyre, distinguished wine historian and Fulbright Visiting Scholar

Why Australian Wine Historian Julie McIntyre is Conducting Her Fulbright Research at the UC Davis Library

“I fell in love with wine, from the grape to its fragrance, before I was legally able to drink it,” explains Dr. Julie McIntyre, historian, scholar and self-proclaimed “wine child,” whose first exposure to viticulture was at her grandparents’ vineyard and winery in Australia.

“As I began my research career as a historian nearly twenty years ago, I could see that investigating the origins and changing patterns of vine growing, wine making, trading and drinking was a new way to see the interconnections between rural Australians and urbanites around the world,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“More recently I have become interested in how the Australian wine industry developed in parallel with international wine science and how wine, as we know it today, is the result of international grape and wine scientists as much as other people in the grape-wine-complex.”

A Fulbright Visiting Scholar from the University of Newcastle, Australia, Dr. McIntyre came halfway around the world to spend several months at UC Davis’ Shields Library, studying the works of the late Professor Emeritus Harold Olmo, particularly his visit to Australia in 1955 — coincidentally also as a Fulbright scholar — and the binational exchange of knowledge and vines that followed. Dr. McIntyre’s visit culminated in a conference called “Wine in the Anthropocene,” at which she convened scholars from six countries to share their wine-related research.

Olmo was one of the foremost viticulturists of the 20th century and a pioneer of the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology. The UC Davis Library, which has been called “the greatest wine library in the world,” houses a vast collection of books and manuscripts on wine history, including the Harold P. Olmo Papers, which are currently in the process of being digitized with the support of a recent gift from the owners of Larkmead Vineyards.

We sat down with Dr. McIntyre to hear more about her research, what she’s been learning, and the path that brought her here to Davis. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Wine: A Manifold Lens

“My Ph.D. work, some years ago now, was where I set about to understand why we even have a wine industry in Australia in the first place. Answering that question requires me to think about society, environments and the emergence of economies. An industry doesn’t just emerge fully formed in a new context.

“Wine is a manifold lens that permits me to look across histories of horticulture, agriculture, consumption and the cultural consecration of particular products. I am thinking about how the commodity-producing communities in regional areas are tied to global currents of economic change, and how it is that people work together or against each other in those contexts to make something as complex as wine. A bottle of wine is only one part of what I study. There really is a much broader and more complex set of ideas going on behind that bottle — and that is what I continue to explore.”

Shaping the modern wine industry through American-Australian scientific exchange, 1955-1977

“In my Fulbright project, I am using the faculty papers of Professor Harold Olmo to understand how knowledge about vine growing and winemaking moved between Australia and America. Harold Olmo is a really crucial node in a global network of people. Even though he published extensively as a scientist for other scientists, there hasn’t been a really close examination of his work for a broader audience.

“I’ve taken a part of Dr. Olmo’s work that’s very significant to me, which is the Australian-American exchange, and I am looking at how that relationship influenced the making of modern wine. The California and Australian wine industries have a parallel history around their approach to the cultivation of vineyards, and they’re not in direct competition in the period I’m interested in, which is 1955 to 1977. There’s a lot of cooperation between Dr. Olmo and some Australian wine scientists. There are also bigger questions to consider about how science and knowledge travel and how they contribute to the changes that we see in an industry.”

The Journey to Davis

“In Australia, I was invited to give a presentation at a conference of international economists that was hosted by my home university. Through that conference, I met a Princeton University economist, Orley Ashenfelter, who founded the American Association of Wine Economists. He suggested that I make contact with Axel Borg at the UC Davis Library about working with some of the materials there. Professor Ashenfelter recognized that I have a particular skill set and a really deep enthusiasm for the sort of work that is possible to conduct here.”

Day in the Life of a Researcher

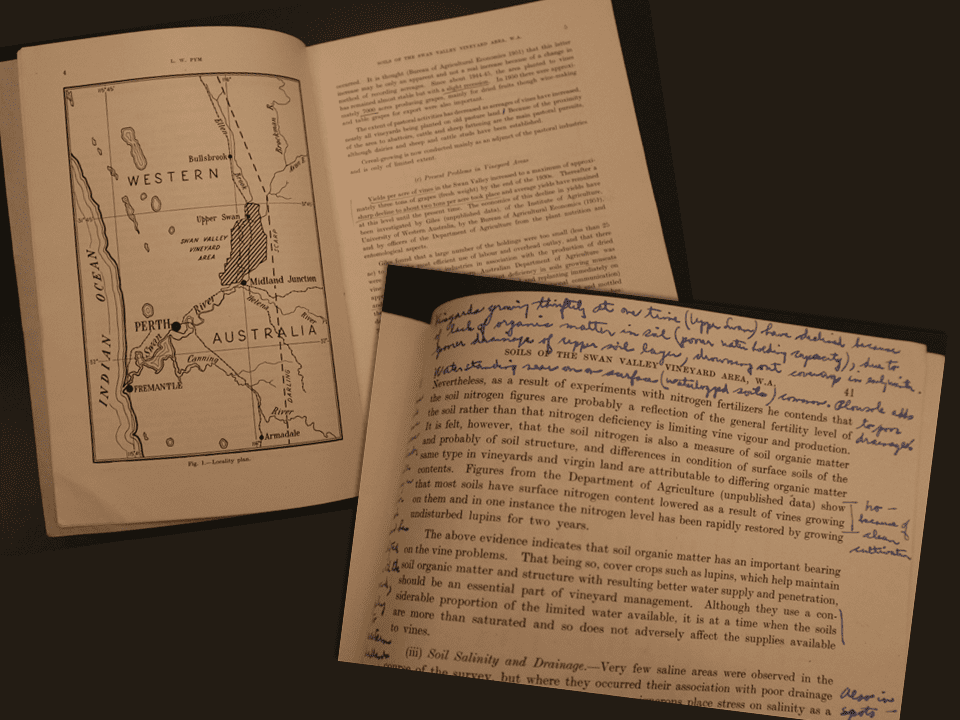

“Essentially, the archival materials are the core of what I’m working with. Notebooks that Dr. Olmo kept during his Australian visit. Letters exchanged between Olmo and others. But I’m also accessing some of the published material in the Amerine Room, which is the most comprehensive collection of wine books in the world. It’s just a tremendous resource.

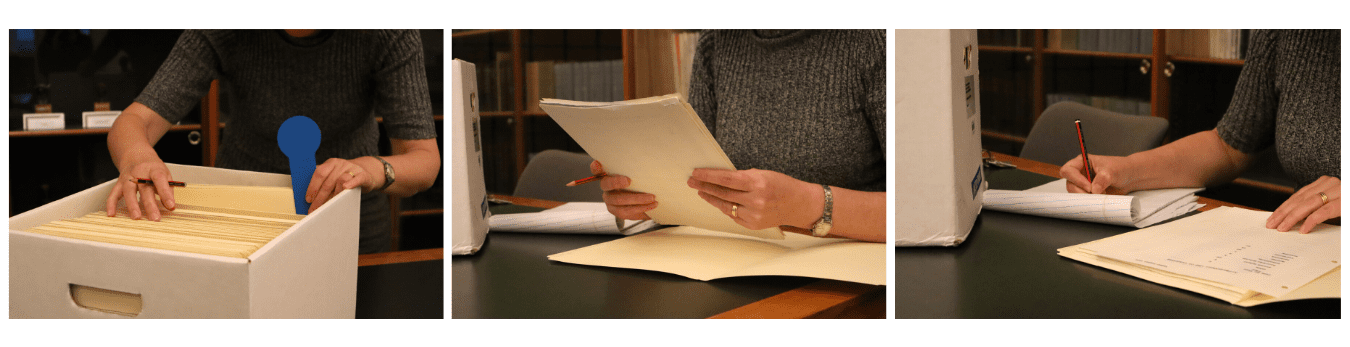

“My work process starts with me taking an overview of what’s in the materials I’ve ordered. For researchers, new archival material is a type of new frontier; until we begin to open up boxes containing folders of documents, we don’t know what’s in them. One of the enormous pleasures of doing the sort of work I do is that I know very few people have looked through these papers. So I have a responsibility to not only read them, but to also develop an understanding of how I can explain to people what’s in them.

“I’m also filtering the materials through my past experience to determine what could be valuable from the records. Actually, a lot of the time that I spend sitting in the room with the materials looks like I’m daydreaming. But what I’m doing is reading intently and then thinking about how I can order that material into an argument about the past, and deciding what else I need to know to make sense of those records.

“For example, as I’ve been working with the archival materials here at Davis, I can see that I would like to write an article on Dr. Olmo’s contribution to grape science. Specifically, in a time when the wine industry modernized through identifying and cloning disease-resistant vines and the development of industrial processes like mechanical pruning and harvesting. So I began to order my reading of material to focus towards that publication. Because there’s no point in me spending time in the archive and doing this reading if I don’t then write about it in a way that reaches and engages a wider audience.

“Because of the international reach and importance of the work by Dr. Olmo and his colleagues, the UC Davis Library’s collections really are distinctive in the depth and breadth of what they offer any researcher interested in the many different approaches we can take to the role of wine as a commodity of economic and social – as well as cultural – significance. Not only in America and Australia, but many other countries of the world.”