17th-century book on distillation in Renaissance Europe gets new life with English translation

In 2010, Darrell Corti, the owner of Sacramento’s Corti Brothers and a food and wine expert, donated a first-edition copy of Io. Bap. Portae Neapolitani De distillatione lib. IX (1608) to the library. The book, which shed light on distillation processes and early science in Renaissance Europe, was gifted in honor of James Guymon, a former UC Davis professor of distillation in the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology Department, and his successor, Roger Boulton.

Io. Bap. Portae Neapolitani De distillatione lib. IX will become more accessible to researchers thanks to UC Davis Classics Lecturer John Rundin, who is in the process of translating the original Latin text into English. Our Archives and Special Collections Student Assistant Raina Cates interprets this Renaissance-era text and discusses Rundin’s interest in its translation.

Distillation in Renaissance Europe: from Ants to Plants

Published not long after the invention of Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press (1450), Io. Bap. Portae Neapolitani De distillatione lib. IX covers all types of distillation, including essential oils and perfumes. Giovanni Battista Della Porta, an Italian scholar and playwright who lived in Naples, wrote the book during the Scientific Revolution and Reformation, a time when distillation was very important in Renaissance Europe.

During this period, Europeans would distill things like ants, fruits and plants to create medicines, cosmetics, poisons, and, of course, alcoholic beverages.

Natural World Reflected in Distillery Apparatus Design

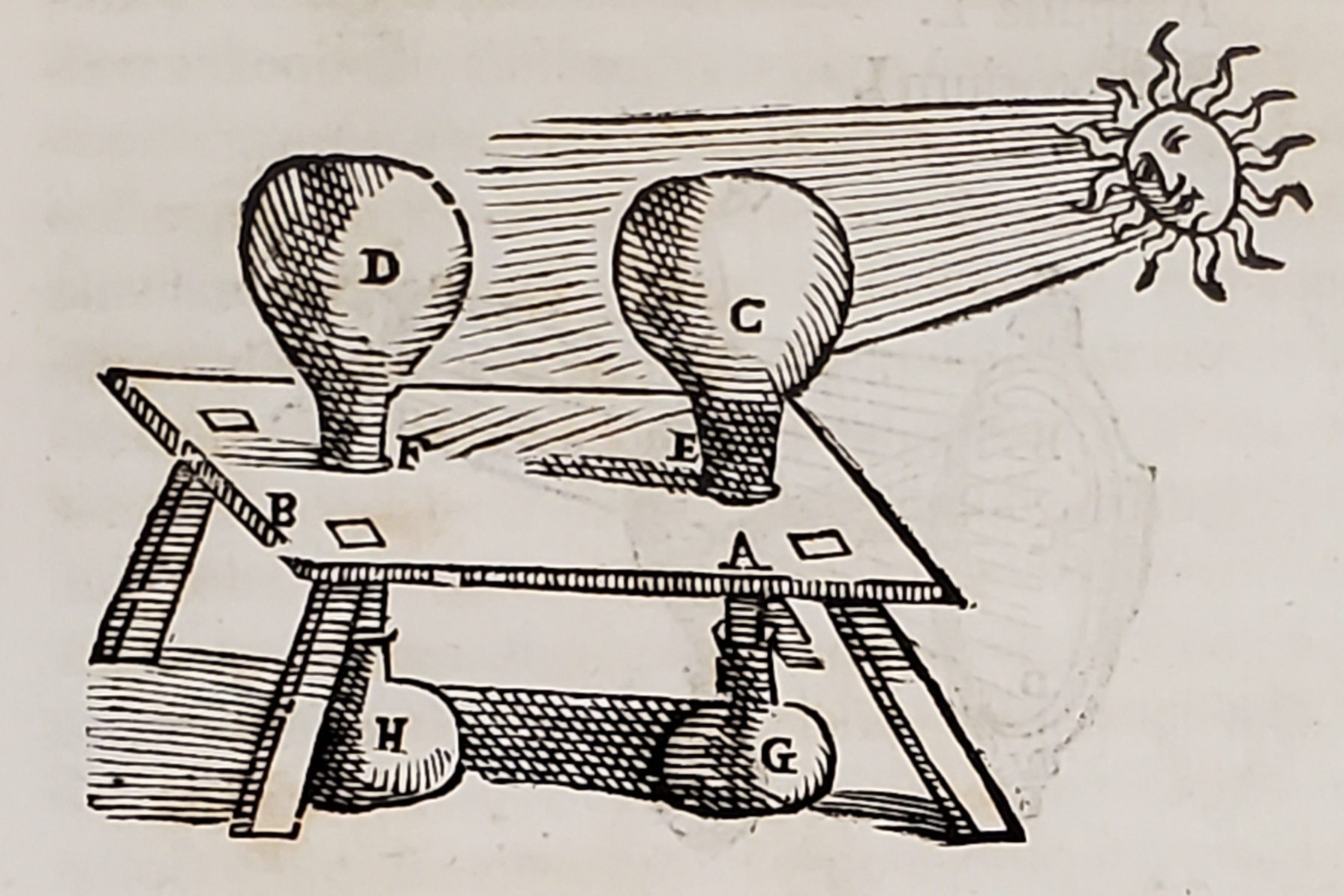

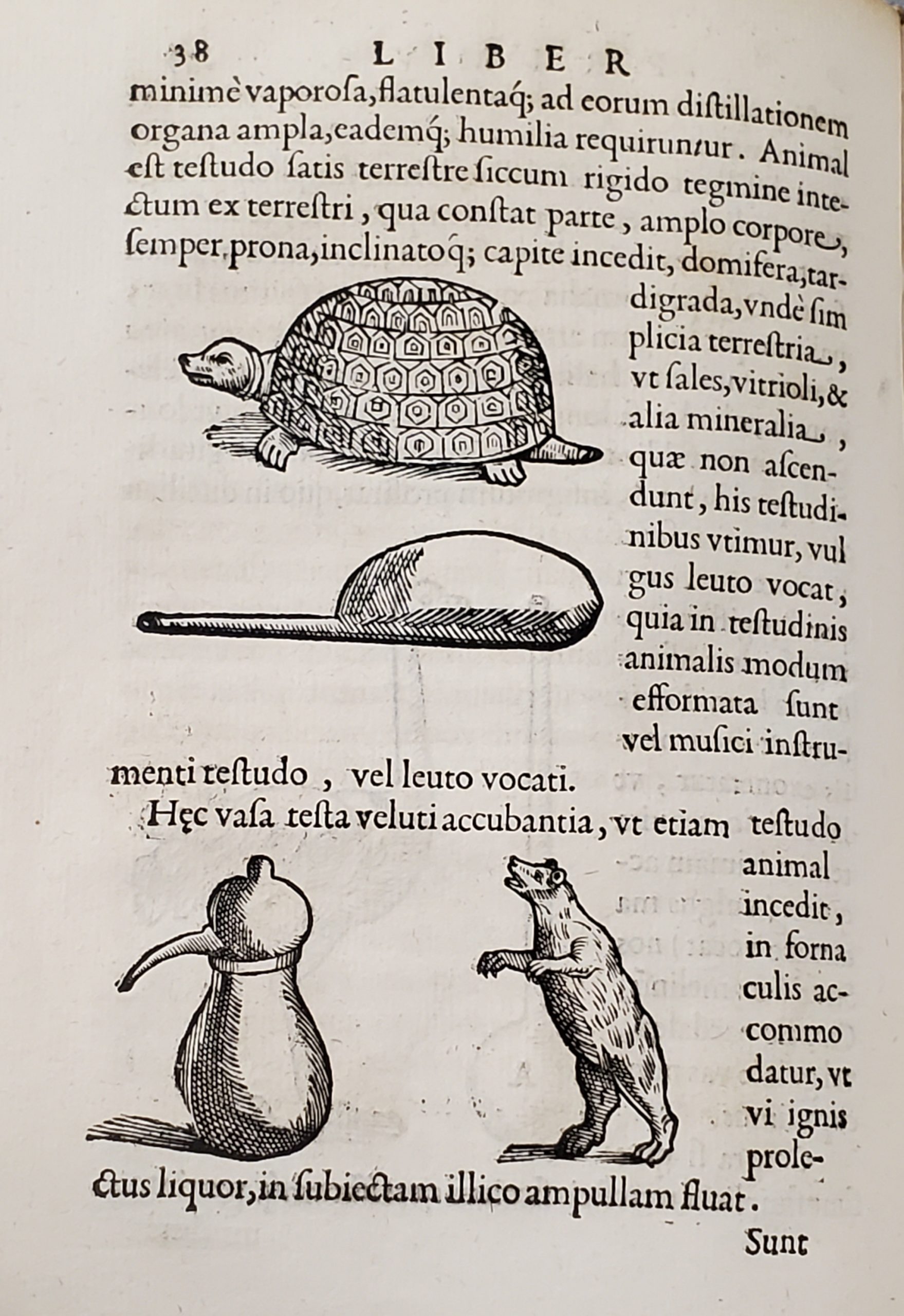

Distillation is a process by which liquid is first purified through vaporization, then condensed by cooling, and finally collected as a liquid. In his book, Porta explains this process through three types of distillery apparatuses that existed at the time: a neck of a vessel that points directly upward; another aiming downwards, and the third shaping gently downward in a slope or horizontal. He compares these vessels to animals, people and other forms found in nature.

Porta explains that these vessels resemble objects in the natural world as a result of their similar dispositions, qualities, and natures. For example, he writes that “in the case of earthy *simples, like salts of vitriol and other minerals, which do not rise, we use these ‘turtles.’ . . . These vessels are put into furnaces with their heads horizontal, just as the turtle walks.”

Classics Lecturer Translating “Historical Monument”

While Porta’s book did not attract the attention of the masses at the time of its initial publication, according to John Rundin, a UC Davis lecturer in classics, “the fact that it was printed by the Vatican’s press in 1608 indicates some importance. Moreover, that it was reprinted in 1609 in Strasbourg indicates some interest, particularly in the Germanic parts of Europe. This popularity in German-speaking Europe is confirmed by the fact that it was translated into German in 1611.”

In undertaking the task of translating the book from Latin into English, Rundin reasons,

“Giambattista Della Porta is an important figure in renaissance Italy, and distillation was an important element in the alchemical world out of which modern science eventually emerged. This is an important historical monument that certainly merits the attention of those who are interested in early science yet who could not read it without a translation.”

For now, you can find the electronic and print versions of Porta’s original book in Latin through the library catalog.

* a medicinal plant, a vegetable drug having only one ingredient

***

Raina Cates is a fourth-year student at UC Davis majoring in International Relations and Cinema and Digital Media. She is also a student assistant in Archives and Special Collections.