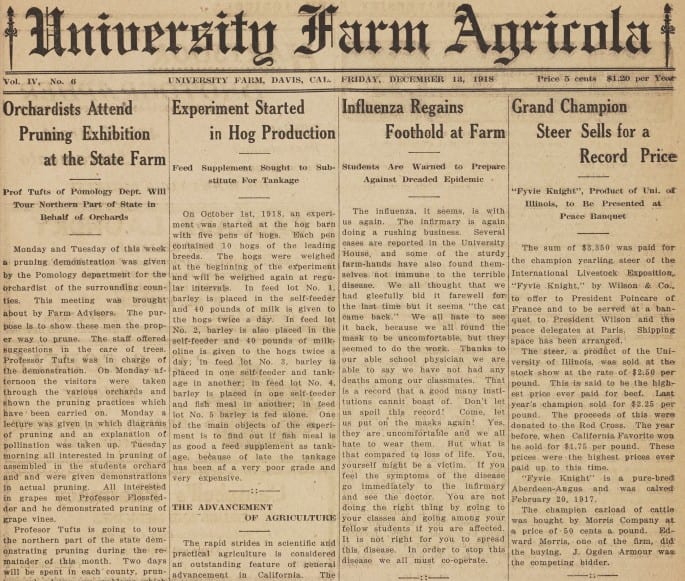

A December 13, 1918, front-page headline from the University Farm Agricola, as the UC Davis campus newspaper was then called, as campus faced a second wave of the Spanish flu (UC Davis Library/Archives and Special Collections)

Trying Times: A Century Between Global Pandemics

Long ago, in the early days of UC Davis (actually, before it was UC Davis — when it was still the University Farm), the Davis community faced a remarkably similar situation to what we are experiencing now: quarantine, cancellation of classes, masks and widespread uncertainty about the future.

In 1918, over a century ago, the Spanish Flu gripped the world and prompted a series of reactions in the Davis community and its campus newspaper, the University Farm Agricola, that were, in many ways, similar to what we are seeing today.

Frustration with masks

In December 1918, a front page story exclaimed:

Come, let us put on the masks again! Yes, they are uncomfortable and we all hate to wear them. But what is that compared to loss of life. You, yourself might be a victim.

A sentence that could have easily been written today as health organizations remind communities to continue to wear masks even as counties progress in opening up.

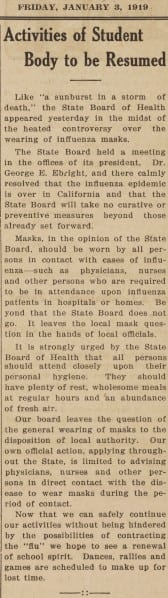

In 1919, the State Board held a meeting that ruled that the worst of the influenza epidemic (as the Spanish Flu was known at the time) was over in California, but recommended that those in contact with compromised individuals, such as health professionals, should continue to wear masks. Like today, communities were eager to get back to their normal day-to-day lives.

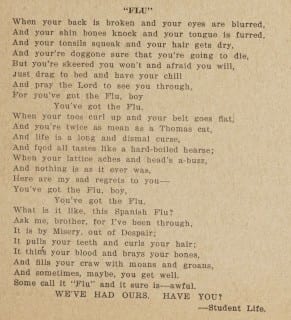

Humor and satire

As an avid Twitter user, I am familiar with the memes, (sometimes dark) humor, and satirical content that have been circulating in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. But even before the age of social media, the internet, or even computers, UC Davis students were able to find humor in the craziness going on in the world. In 1919, the Agricola jokingly suggests the following “cure” for the Spanish Flu:

…to get rid of me you must first starve and then live on pills and hot water bottles and num vomica and then maybe a little soup and if your fever goes down you can have some mush and fresh air but if you are not careful I’ll get you again.

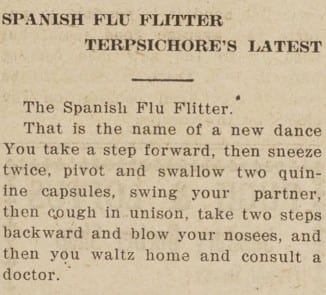

Another Agricola writer describes a dance called the “The Spanish Flu Flitter”:

take a step forward, then sneeze twice, pivot and swallow two quinine capsules, swing your partner, then cough in unison, take two steps backward and blow your noses, and then you waltz home and consult a doctor.

Yet another concludes a satirical poem describing the inevitable flu symptoms with “we’ve had ours. Have you?”

As that line suggests, one difference between attitudes back then compared with today seems to be that now, most people (and public policies) are aiming to keep people from getting COVID-19 until a vaccine can, hopefully quickly, be developed. By 1919, several of the writers took a humorously fatalistic attitude that essentially implied, “we’re all going to get it, so you might as well get it out of the way sooner rather than later.” Perhaps in an age before medicine was as advanced as it is today, students were simply trying to accept and cope with what seemed inevitable.

Fear of a second wave

Although the Spanish Flu hit UC Davis in early 1918, there was a resurgence on campus in December of 1918. The Agricola wrote:

We all thought that we had gleefully bid it farewell for the last time but it seems “the cat came back.’’

The student writes that unlike many institutions, UC Davis had not yet experienced any deaths due to this resurgence of influenza and pleads that students continue to wear masks in order to not spoil this record.

Looking back, looking forward

As we come toward the end of the COVID-19 remote Spring Quarter, and the campus moves into “phase 2” of a gradual reopening and develops its plans for the Fall, it is illuminating to look back on how the campus responded to the last major pandemic that shook the UC Davis community and the world — almost exactly a century ago. As we’re looking back, we can only wonder if we are also seeing similarities with what is to come.

Fiona Micoleau is a senior at UC Davis majoring in communications and professional writing, and a student employee of the UC Davis Library.

From the Archive

Click any of the clips below to read the full story in The Aggie Archive.