Preserving the Past to Ensure a Future of Discovery

Preservation Lab safeguards, extends longevity of library's research collections

As organic materials made of wood or cotton pulp, leather, cloth and glue, books are constantly under threat to agents of deterioration: extreme swings in humidity and temperature, light, pests (silverfish, moths and rodents among others), packaging, page acidity, and human-made and natural disasters. All wreak havoc on a book’s longevity, individually and collectively.

Jennifer Jouas Viall is well versed in these threats, and battles them daily in her role as the UC Davis Library’s Preservation and Conservation Specialist.

Jouas Viall, who joined the library team in 2022, is responsible for the present health of our physical collections — the thousands of books that you find throughout the Shields Library’s stacks, as well as the books, photographs and materials held in our Archives and Special Collections — and for extending their life expectancy well into the future.

Her work, which takes place in the Margaret B. Harrison Preservation Lab in Shields Library, is largely a behind-the-scenes operation that goes unnoticed by the public. Yet, it’s critical to the mission of a research library like ours: ensuring our collections are available for use.

A damaged book can’t be used, can’t be researched. My job is to assess and fix damaged books so they can get back in the stacks, and accessible to researchers and visiting scholars.”

Jennifer Jouas Viall, Preservation and Conservation Specialist

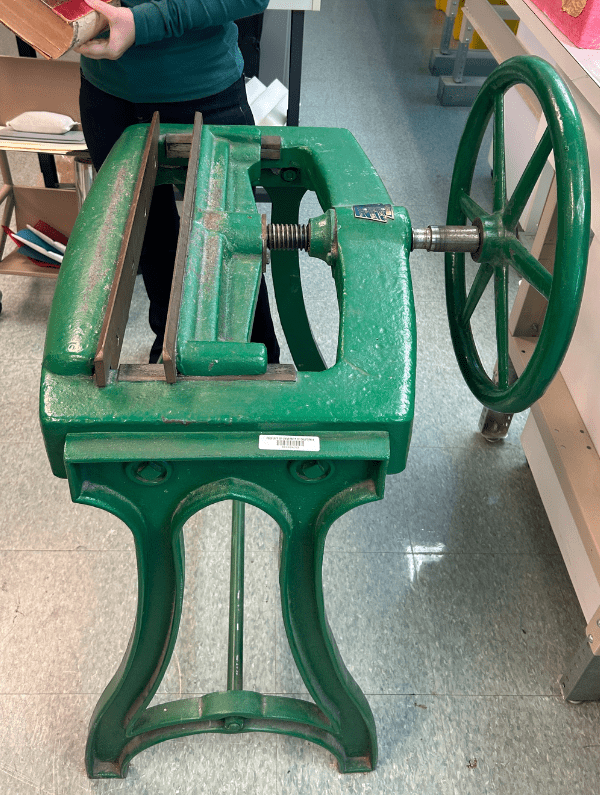

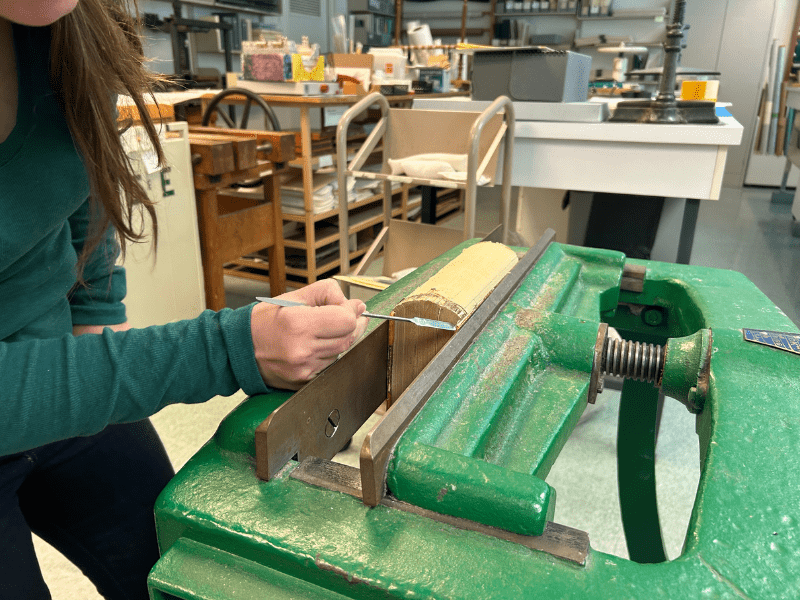

Named in honor of long-time library supporter and hand bookbinder Margaret B. Harrison, the Preservation Lab is a large space anchored by a large repair station. A hodgepodge of modern and antique bookbinding machinery (the latter donated by the Harrison estate) surround the station, along with bins of paintbrushes, a mini-refrigerator of archival glue, shelving drawers of Japanese tissue papers and projects in the queue.

At the lab, Jouas Viall is currently in the process of establishing a workflow for damaged books in the general collections — assessing and making recommendations for what can be kept and repaired in house or sent to a bindery, and what can be discarded.

She is also training a student assistant to help repair general collections books. On any given day, treatments might include tip-ins (gluing loose pages back into book), hinge repair (damage on the inside of a book spine), tear repair with Japanese tissues, and re-backing (using cloth to fix the spine).

In treatment

Jouas Viall’s preservation work with books, photographs and items held in Archives and Special Collections requires an interdisciplinary set of skills. Whether she is repairing delicate spines, deacidifying pages, or matching a historically accurate color of decorative paper to a book’s binding period, her treatments demand the precision and dexterity of a surgeon, the curiosity and creativity of an artist and art historian, and a chemist’s expertise in paper degradation.

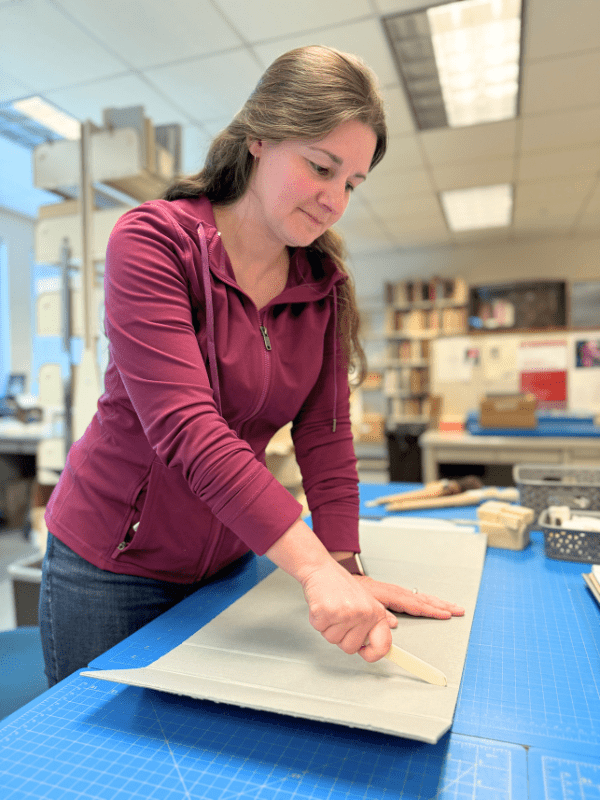

Her spatial awareness is also an asset. Jouas Viall can look at a flat item and immediately visualize it in 3-D, a skill she uses frequently in the building of phase boxes, custom enclosures used to better protect rare, heavily used, or unusually sized books and items from deterioration. She once built a phase box for an 1880 Spanish sword.

Of the many tools she uses in her trade, a bone folder — a dull-edged hand tool used to fold and crease materials in bookbinding — is her favorite.

“It’s so versatile,” says Jouas Viall. “I use it for making protective enclosures as well as repairing the spine of a book, paper and tears.”

Rare repair

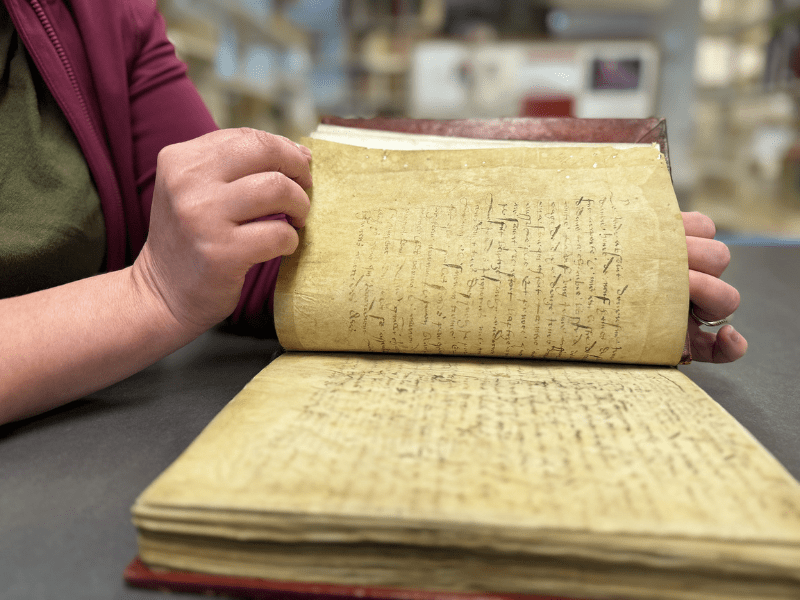

Repairing rare items is slow, meticulous, hands-on work. It requires patience and time management, with more complex treatments applied in stages and taking several months or more. Jouas Viall recalls repairing an especially fragile 18th century book earlier in her career.

“It was a high-need book in animal husbandry, and researchers couldn’t use it because it was in such a fragile state,” says Jouas Viall. “It took me a year to take it apart, dry clean and then wash each page, repair each folio, sew it and rebind it.”

A successful treatment, according to Jouas Viall, balances authenticity and usability.

Our special collections items have to be touched, have to be used. My role in treating these items starts with investigation, and then applying the least invasive treatment that I can to make it accessible while respecting the item’s provenance and history.”

Jennifer Jouas Viall

In fact, many of Jouas Viall’s treatments are reversible. She approaches each treatment so that in 50 years, a future conservator might be able to “undo” past treatments and use modern methods to stabilize the item.

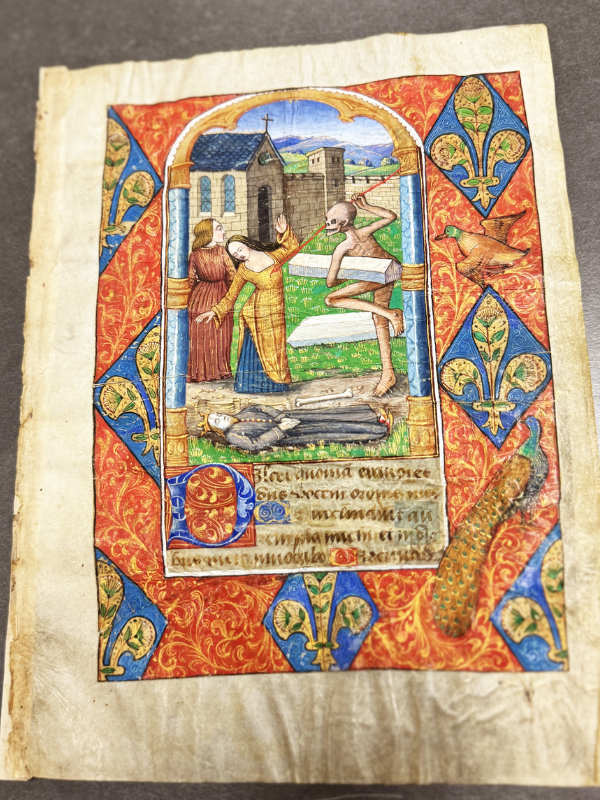

Later this spring Jouas Viall will be working on a repair of The Book of Hours, a 13th century prayer book written on vellum with gold leaf and painted art. Catholics used the book to follow and express their devotion to the Virgin Mary by setting aside certain times throughout the day to recite services.

It’s possibly the oldest item she’ll treat in her career, and also the most challenging, due to complexity of the binding and the age of the item.

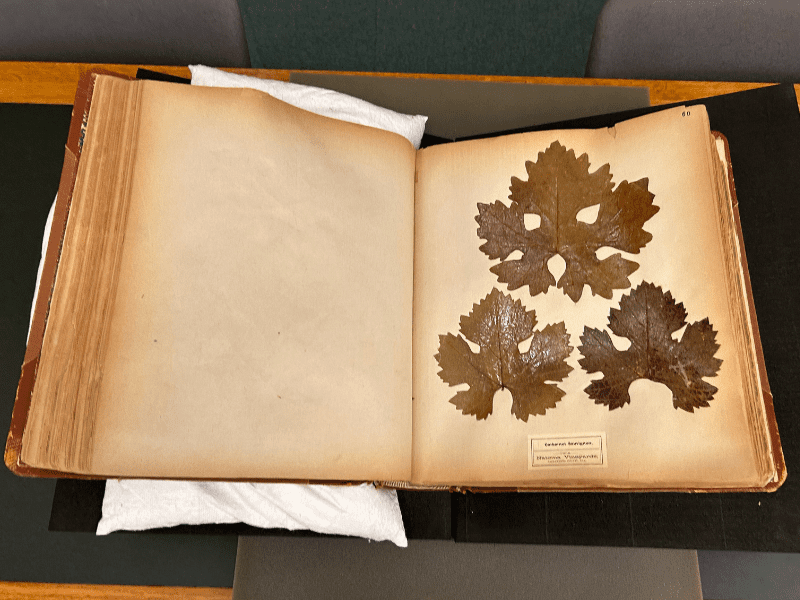

Other projects in her queue: a one-of-a-kind wine book with pressed grape leaves that needs to be cleaned and its structure resewn and repaired, as well as a new clamshell enclosure for the library’s Sumerian Clay Tablet to make it more stable for display.

Environmental standards to emergency response

In addition to hands-on, physical treatment of damaged books, Jouas Viall is developing environmental standards for the Archives and Special Collections closed stacks, focused on stabilization and damage prevention. The gold standard, according to Jouas Viall, is to ensure items last 100-150 years.

If you’ve ever visited the closed stacks, that slight chill you feel is not by accident. Shields Library’s goal is to maintain a stable temperature in the space of 62 degrees (plus or minus 3 degrees) with 40-50% relative humidity.

“We now have a cloud-based climate system with monitoring sensors,” says Jouas Viall. “I check the metrics weekly and get notified if there are fluctuations outside of our set range, even if we lose power.”

Jouas Viall is also developing emergency response protocols for the collections — how to salvage wet books and prevent mold if a water pipe bursts, for example.

Preservation tips at home

If you have family heirlooms at home like books, newspapers, photographs and clothing, there are steps you can take to extend their longevity. Heirloom preservation can be expensive, says Viall, so she recommends starting small and focusing on one area. Some tips:

- Check consumer sites for at-home preservation kits and made-to-measure book boxes.

- If you have photos in binders, put them in photo-safe plastic sleeves such as polypropylene, polyethylene, or polyester sheeting.

- Keep books where temperature and humidity are the most stable – not the attic or basement.

- Store items in acid-free boxes and folders which protects them from dust and light.

- Digitize or photocopy your items if possible.

- Avoid use of paperclips, rubber bands and tape.

- Seek out a professional if repairs or treatments are needed.

This post was written in celebration of Preservation Week, an annual event hosted by the American Librarian Association to raise awareness of the role libraries, museums and other cultural institutions play in preserving archives and collections.