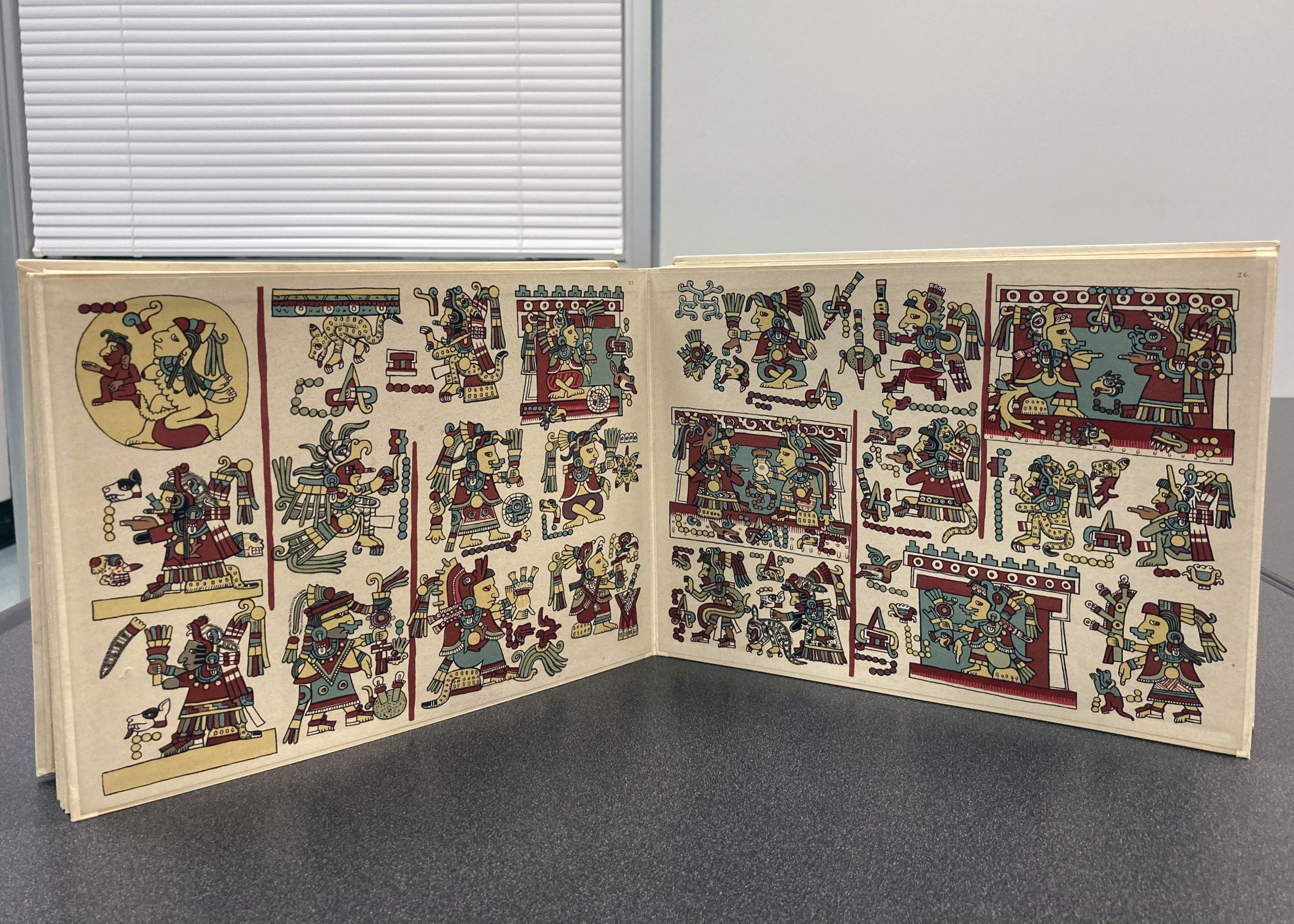

Codex Nuttall marriage ceremony

Archives in the Classroom – Tips on Approaches for Students and Instructors

Did you know that our Archives and Special Collections librarians collaborate with instructors from UC Davis? They provide students with hands-on learning experiences and skills in using archival materials including primary sources. They conduct anywhere from 40 to 50 classes every year ranging in topics from artificial intelligence to medieval to renaissance art, from winemaking to printmaking and bookmaking, from conspiracy theories to culture and diversity, or from Victorian serial fiction to the history of visual communication. Students benefit from using the archives by getting direct opportunities to interact with evidence of human activity. Through analysis, students study eye-witness accounts in unique formats and further develop critical thinking skills as they sift through creators’ intents and biases and learn to navigate through other types of information sources.

This week and next, we’ll showcase two pieces from the archives and discuss approaches we take to teaching with them.

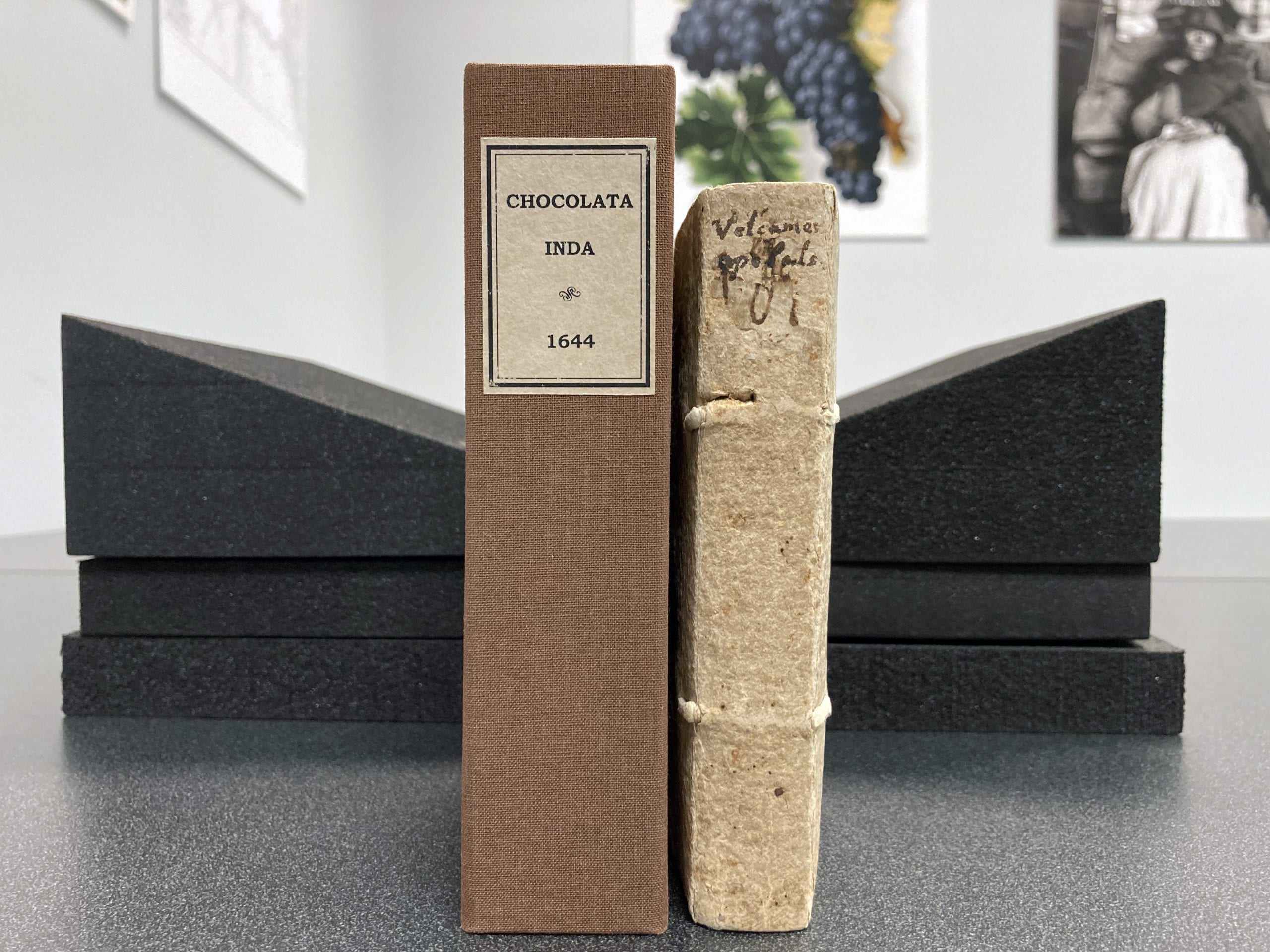

Today, the topic is chocolate and traditions related to its presentation and consumption. We look at two rare books about chocolate, Chocolata inda: opusculum de qualitate & naturâ chocolatae, by Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma, and the Codex Nuttall. Christine Cheng, the Library’s Instruction and Outreach Librarian, previously wrote blog posts about the history behind these two books, and points out questions that often come up in class discussion.

Christine Cheng, Instruction & Outreach Librarian for Archives and Special Collections:

I enjoy featuring the above two items in classes because not only do they contain related topics in content, but their physical forms also aid in the study of the materiality of books.

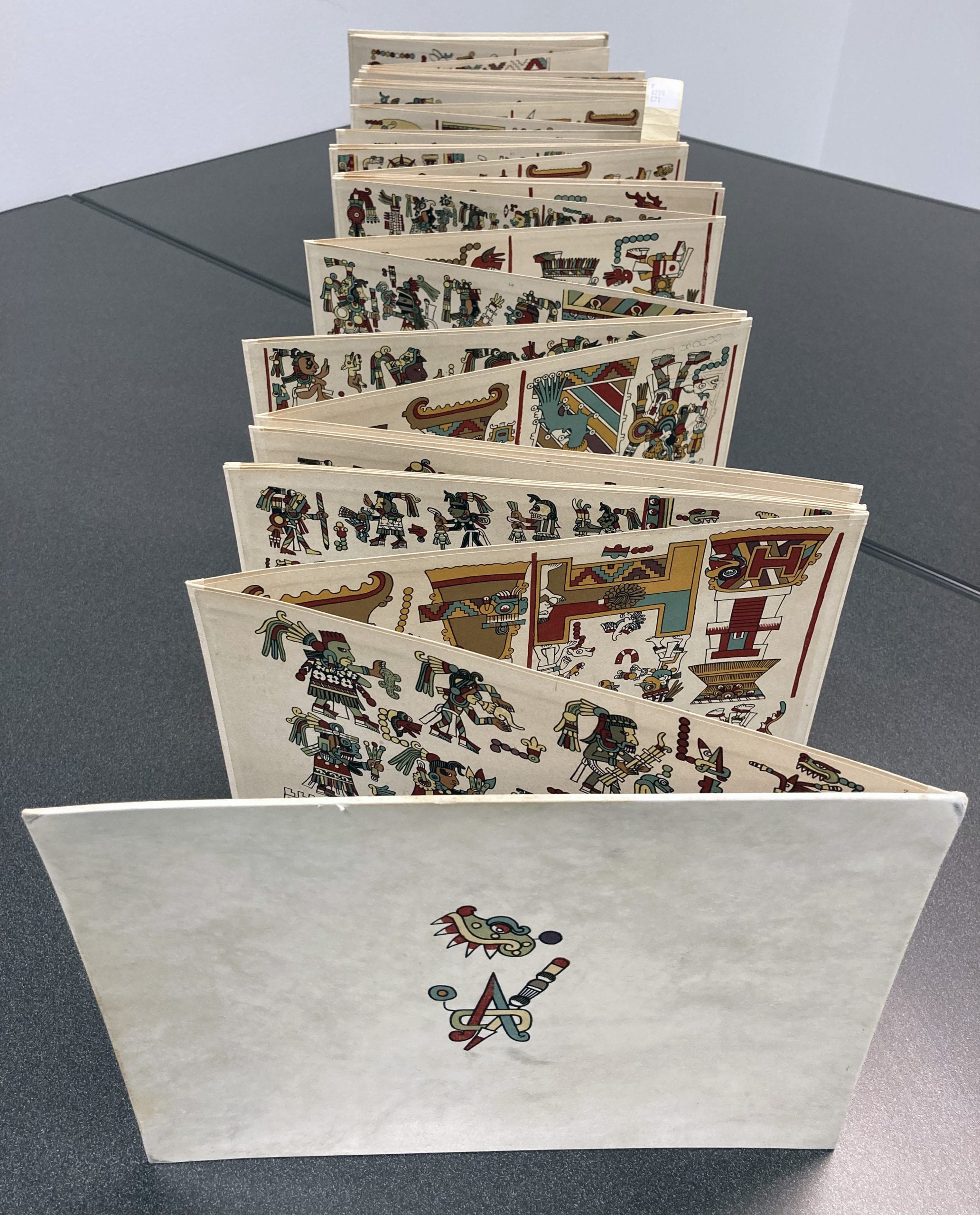

We’re already familiar today with how sweet chocolate tastes as well as with its common solid form. To introduce something different, I like showing students evidence of how chocolate was originally consumed as a bitter drink. After visiting sick patients on a hot day in Chocolata Inda, physician Colmenero wrote about drinking chocolate for the first time, noticing how it soothed his stomach and slaked his thirst. Mesoamericans originally drank and enjoyed chocolate for its therapeutic effects. The ingredients typically included spices and the drink was reddish in color, topped with a foamy froth, and required special drinking vessels. A pictorial representation of this is featured in a page from Codex Nuttall of a marriage ceremony:

We can see the drinking vessel and frothy head more clearly below:

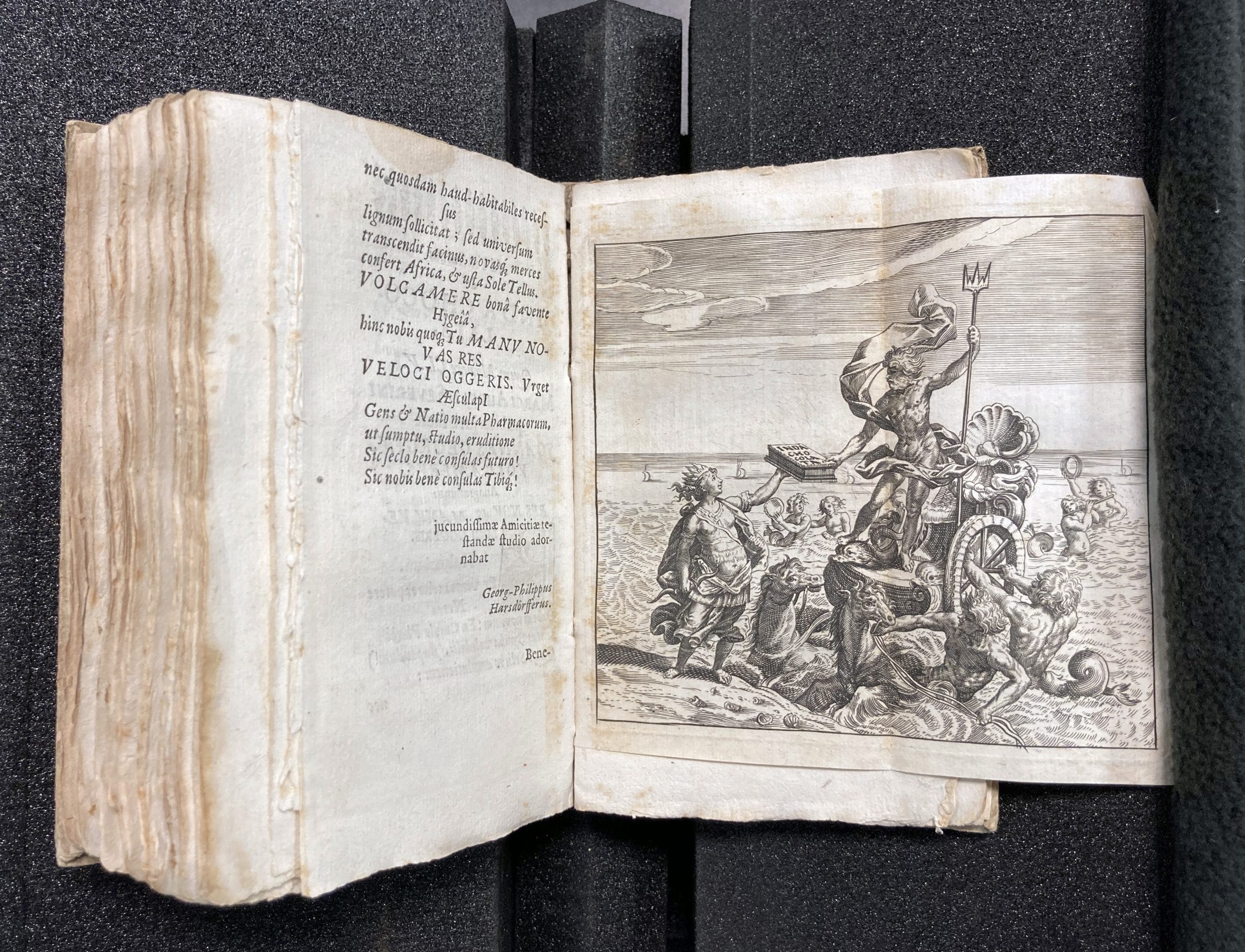

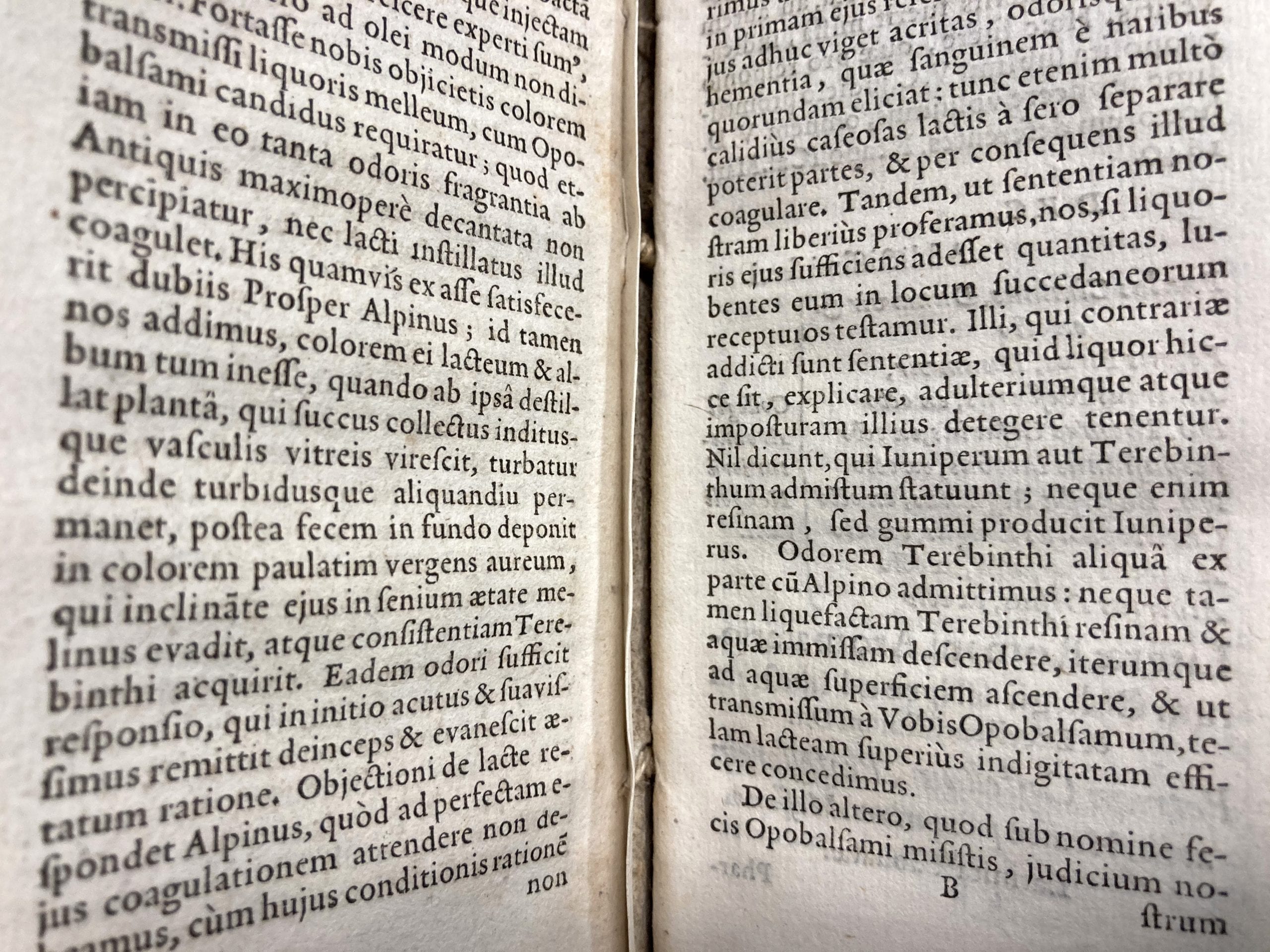

Compare and contrast this with the frontispiece from Chocolata Inda:

The image features a Native American who represents the New World, giving a gift of chocolate to Neptune, god of the sea, who represents the Old World — or, as described in the catalog, an “allegorical copperplate engraving of Neptune receiving chocolate from Mexico.” In another interpretation, it points to the divine origin of chocolate as a gift from the gods. While the final interpretation can be open to debate, we know for certain that the image is misleading: the chocolate should be presented in a drinking vessel since it was consumed as a beverage before 1800.

Primary vs. Secondary Sources

Apart from learning about the original consumption of chocolate, we can use both items to consider what makes a source a primary source or a secondary source. For example, Chocolata Inda is a Latin translation that was published 13 years after the original Spanish work, while Codex Nuttall is a facsimile of the original. Are both considered to be primary sources? Does it depend on the context, purpose of use, or how much time has passed between the original and following work?

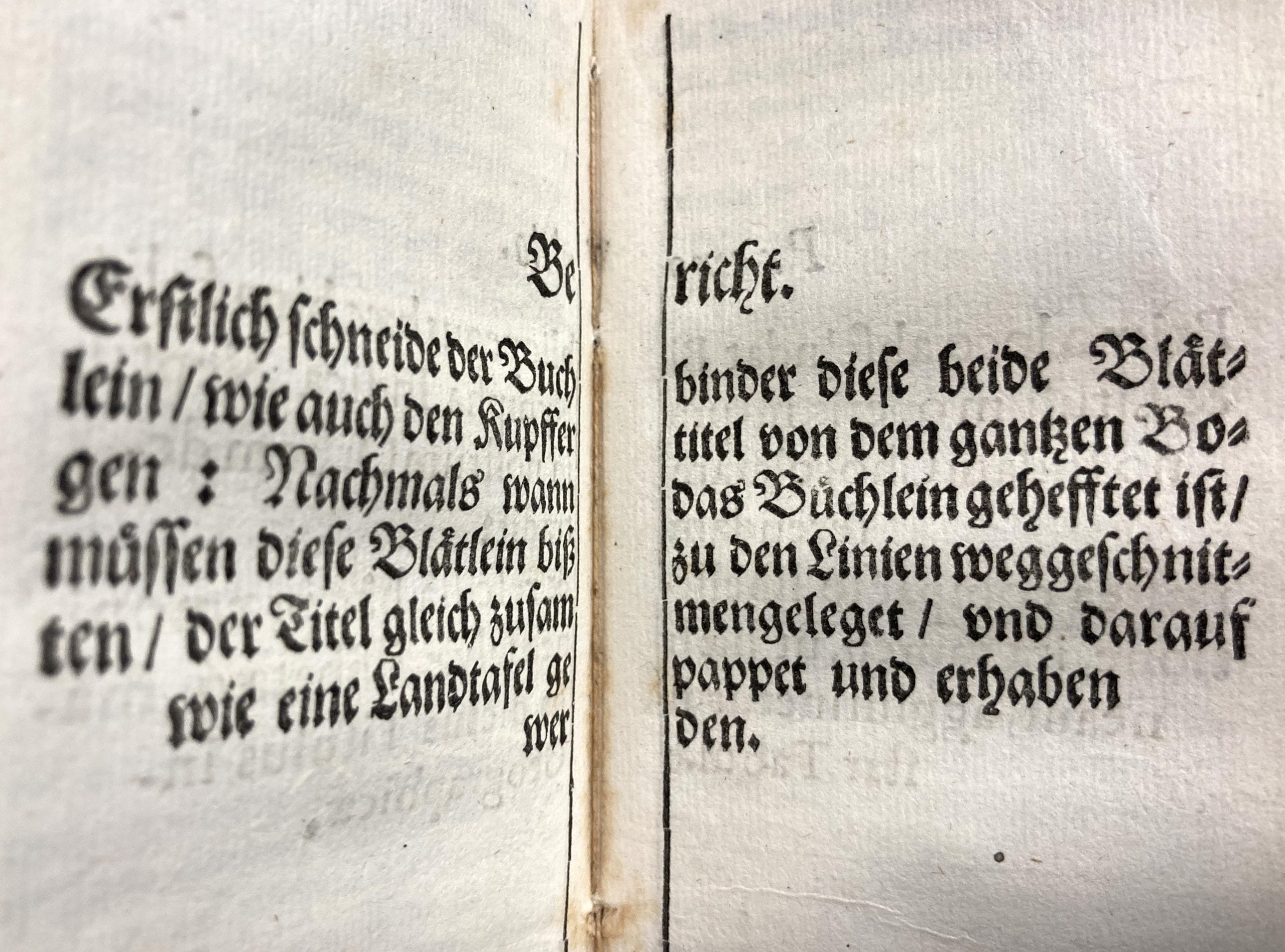

We can also do an analysis of the physical qualities of Chocolata Inda by examining pagination (or lack thereof), signature marks, catchwords, its spine and overall binding, as well as printing mistakes.

Judging a Book By Its Cover

With Codex Nuttall, students can think about whether it fits the definition of a codex. Should we categorize the screenfold format as a type of book form? Rather than being made of individual sheets/pages bound in a center, Mesoamerican screenfolds were made of animal hides that were accordion-folded when stored, but displayed the pictography all at once when unfolded into a continuous strip. The Codex Nuttall comprises 47 sections of deer skin and is one of few surviving screenfolds from the pre-Hispanic/pre-Columbian period. In descriptions of the conquest of the region, Spaniards referred to these screenfolds as “libros” (books). The original Codex Nuttall is preserved and held at the British Museum. Considering colonization and its impact on indigenous peoples, cultures, and records brings more questions to the surface.

After learning about screenfolds, students can return to the frontispiece from Chocolata Inda to further analyze depictions of the Americas, indigenous peoples and lands, and think about how a Eurocentric view used specific imagery to promote the New World.

The last aspect I’ll focus on is using both items to study how readers interacted with texts. Are there marginalia, commentary, or other markings in Chocolata Inda? How is this sort of engagement with the text similar or dissimilar to Mixtec writing where the pictograms in Codex Nuttall were written with the intent to be performed?

Finally, what other questions come to mind when thinking about the text, content, and materiality of these two objects?

Works cited

Boran, Dr. Elizabethanne. “Chocolate is good for you – according to Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma’s Chocolata inda. (Nuremberg, 1644), 12o.” Edward Worth Library. Accessed February 10, 2021. http://edwardworthlibrary.ie/book-of-the-month/2012-books-of-the-month/2012-march-book-of-the-month/

“Mesoamerican Screenfolds.” Mesolore. Accessed February 10, 2021. http://www.mesolore.org/tutorials/learn/10/Mesoamerican-Screenfolds