Codex Nuttall, F1219 .C71, Special Collections

50 Features of Special Collections: the Story of Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw

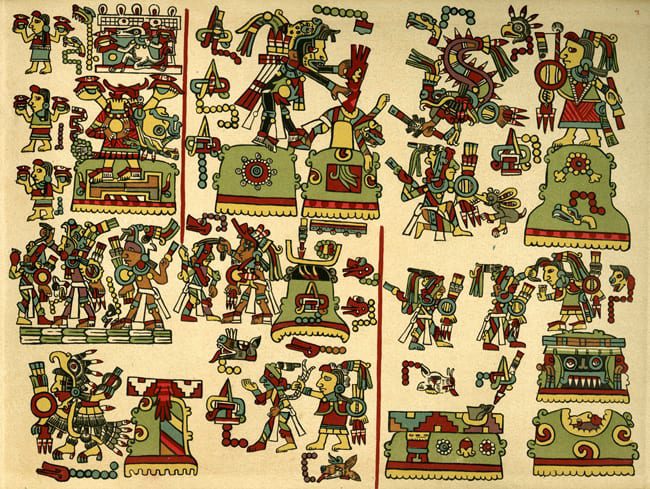

It is extremely rare to find manuscripts from the pre-Hispanic times of the Mixtec Indians since the conquistadores destroyed most of their records during the Spanish Conquest. In Robert Lloyd Williams’ The Complete Codex of Zouche-Nuttall, Williams lists the Codex Nuttall as one of five major Mixtec pictogram codices: Selden, Bodley, Zouche-Nuttall, Vindobonensis Mexicanus I, and Codex Alfonso Caso. The screenfold manuscript book, which comes from what is now Oaxaca, Mexico, comprises 47 leaves (one leaf equals two pages of a book, one on each side) made of deer hide and contains vibrant, painted images of Mixtec pictography. According to Williams, this type of pictogram writing was used as a tool in oral traditions to assist bards in reciting stories from memory, “the pre-Hispanic manuscripts were written to be read and performed but not written specifically for us to read.”

The story of how this ancient Mexican codex ended up in a Dominican monastery in San Marco, Florence in 1859 is unknown. Sir Robert Curzon, 14th Baron Zouche, received it as a gift, then loaned it to the British Museum. After his death in 1876, his sister inherited the codex and donated it to the Museum in 1917. While the original codex remains in the British Museum, Special Collections holds the facsimile, Codex Nuttall, published by Zelia Nuttall in 1902 with the support of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. It is largely due to her efforts – through the hiring of two British artists to copy the manuscript, then pushing for its publication – that the world knows about and can study this codex.

The Codex Nuttall holds two narratives: on one side (the older side called the obverse), there is the history of Mixtec events and important hubs in the Mixtec region, while the other side (the reverse) depicts scenes of Eight Deer’s military and political conquests, adventures, ceremonies, and genealogy records.

In contrast to a typical book where it’s read from left to right, the codex reads from right to left starting from the top right-hand corner, following the column down from top to bottom, and then over to the next column on the left from the bottom to the top. The red lines serve as dividers within the narratives as can be seen in the following examples:

Page 3 (obverse): The War from Heaven – War with the Stone Men in the Northern Nochixtlan Valley at Yucunudahui:

Page 16 (obverse): Featuring Lady Three Flint Elder and Lady Three Flint Younger:

Page 27 (obverse): From Tilantongo to Teozacoalco – presenting the other wives of Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw, as well as the children of Eight Deer and Five Eagle:

Page 37 (obverse): After Leaving the Cave and At Sayutepec:

Page 69 (reverse): Eight Deer in his animal spirit form battles an eagle, a dog is sacrificed, and Lord Nine Flower (Eight Deer’s brother) sacrifices a man:

Page 81 (reverse): The Assassination of Lord Twelve Motion and the Siege of Hua Chino:

Works consulted:

Nuttall, Zelia, Zouche, Robert Curzon, Baron; Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. Codex Nuttall: Facsimile of an Ancient Mexican Codex Belonging to Lord Zouche of Harynworth, England. Cambridge, Mass, 1902.

Williams, Robert Lloyd. The Complete Codex Zouche-Nuttall: Mixtec Lineage Histories and Political Biographies. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013.

The Codex Zouche-Nuttall. The British Museum. Accessed February 3, 2017.