Scholar and Author

Betita was the first Latina to graduate from Swarthmore College. She received her bachelor’s degree with honors in History and Literature.

In the year 2000, Swarthmore bestowed her with an honorary doctorate. Here is an excerpt of her speech to the graduating class:

“Being part of the global human struggle for social justice can bring a sense of personal fulfillment and happiness. I deeply hope all of you graduates may someday know that kind of happiness. It is all too clear today that the struggle for social justice and to defend our planet is far from over. But all over this country — and other countries too — young people are on the move with a new passion. Here in the U.S., they are fighting for decent schools, for ethnic studies, for worker’s rights, against sweatshops, against the criminalization of youth — on many, many fronts, across the whole nation. They are smarter than we were in the 1960s, and the young women are playing leading roles. So I want to thank these youth above all. For their spirit, energy, and determination. For their refusal to accept injustice and their love of justice. They can carry us all forward.“

An Indelible Legacy of Scholarship

Betita left an indelible legacy in her Chicanx and Latinx communities through her decades of scholarly activism in the Chicanx Movements and through her publications which helped shape Chicanx Studies as a field. In the year 2000, shortly after the publication of De Colores, the National Association of Chicana and Chicano Studies awarded Betita the Scholar of the Year Award.

Excerpt from the Foreword to De Colores Means All of Us written by Angela Davis:

Elizabeth Martínez’s work comprises one of the most important living histories of progressive activism in the contemporary era… her writings record countless struggles for social justice…offering us an invaluable reader in the rich history of radical activism in the Americas…

Here, then—for all our benefit—in all her glory, is the inimitable, the irrepressible, the indefatigable Betita Martinez.

Betita embraced her Chicanx/Latinx communities. She was committed to transform the very conditions that make possible the exploitation of our peoples. She felt tremendous pride for her cultural and indigenous roots; she loved mariachi music and always pushed for Spanish language accessibility and bilingual publications.

In 1968, Betita moved to Albuquerque where she joined the Chicanx Movement. There she became the founding editor of the leading movement newspaper, El Grito del Norte. She also co-founded the Chicano Communications Center in 1973 that used theater, music, and activist speakers to educate la Raza about their histories and the issues they faced.

As Olga Talamante describes, Betita taught women how to write their stories and instilled a vital sense of unity among Chicanas. She printed many of their stories in El Grito del Norte. The collection of first-person narratives shaped how Chicanas saw themselves and inspired Chicana feminist consciousness. These early Chicana writings informed future feminist and ethnic studies research methodologies and pedagogical practices that center the transparency of the situated first-person account in knowledge production.

Viva la Raza! The Struggle of the Mexican-American People, the book Betita co-authored with Enriqueta Vásquez in 1974, extends this first-person narrative into the first-person plural in what we might now reference as a type of historical writing that converges with the now recognized literary genre of Testimonio writing. As Annemarie Perez describes this intervention in Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Avtivism and Feminism in the Movement Era, Betita and Enriqueta write about their own history in structural defiance of the existing dominant structures of historical writing. In so doing, they “silence Anglo scholarly authority while asserting their own,” claiming their own history and identities as Chicanas.

In 1971, Betita published her pivotal essay in El Grito entitled Viva La Chicana and All Brave Women of La Causa (which you can read here thanks to the digital archival work of Chicana Por Mi Raza). Below is a selection of excerpts that are as relevant today as they were in 1971.

All over the country today, La Raza is in motion.

A spirit of awakening runs through the big city barrios, small towns,

colleges and universities, the countryside. Our people are refusing

to be filled with shame any longer, they are refusing to be oppressed,

they are demanding liberation and a decent life.

Betita then writes of the ways Chicanas are organizing themselves to fight for better working conditions and pay, for access to education, welfare rights, better housing and child care, and for an end to police brutality. She invokes the tradition of strong Chicanas in northern New Mexico who “draw strength from their closeness to la tierra/the land” and proclaims: “we can learn much from them.” She concludes with a testament to revolutionary Chicana politics:

Revolutionary Chicanas want the liberation of our people

and of all oppressed peoples…

We do not want a few Chicanas to get better jobs, higher salaries

while everyone else continues to be exploited…

Revolution means turning things upside down…

revolution means new ideas

about relations between men and women, too.

I remember Betita exactly like this.

I can almost hear the sound of the phone ringing; I can feel the warm afternoon sunlight trickle in.

Betita’s home was filled with an interesting pairing of the bustling energy of work getting done—files, newspaper clippings, ringing phones, people coming and going, and a serene breeze coming in from the garden and landing on her devoted dog Xochitl at rest on the floor.

“She was an elegant presence and a dynamic soul.”

—Photographer Janis Lewin

Betita’s Opus

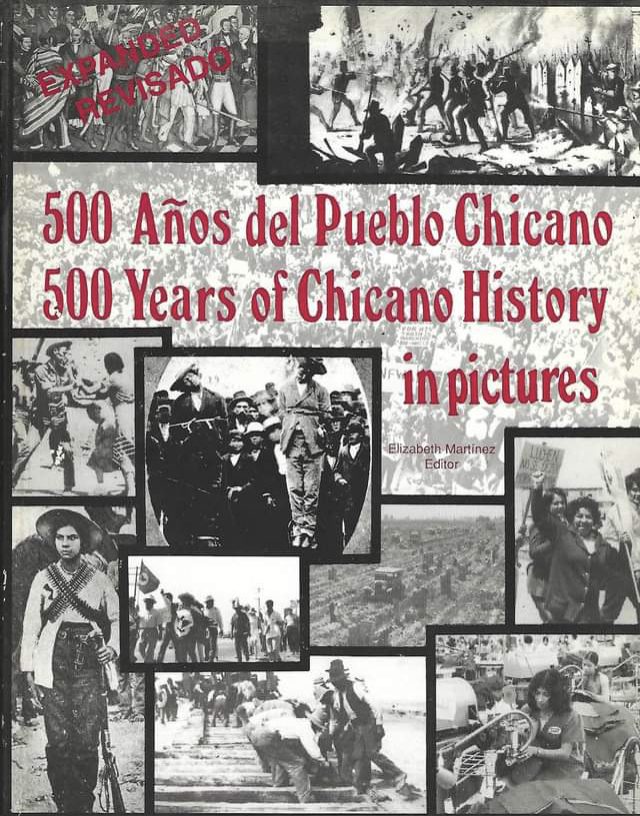

Betita’s publication efforts were often a community organizing and mentoring process. She compiled a huge team in the production and grassroots fundraising efforts to publish her great opus, 500 Years of Chicana Women’s History/500 Años de la Historia de la Mujer Chicana, which received the 2009 AUUP’s Best of the Best Outstanding Book Distinction.

Chicana writer and feminist activist Cherríe Morage writes this about the book: “I thought I knew my history, but 500 Years taught me more than I could imagine. In these pages la Chicana emerges from historical erasure as spirit warrior, artist and revolucionaria.”

Betita herself described the book this way:

“500 Years of Chicana Women’s History is a vivid, pictorial account of struggle and survival, resilience and achievement, discrimination and identity. The bilingual text, along with hundreds of photos and other images, ranges from female-centered stories of pre-Columbian Mexico to profiles of contemporary social justice activists, labor leaders, youth organizers, artists, and environmentalists, among others. In the section on jobs held by Mexicanas under U.S. rule in the 1800s, for example, readers learn about flamboyant Doña Tules, who owned a popular gambling saloon in Santa Fe, and Eulalia Arrilla de Pérez, a respected curandera (healer) in the San Diego area. Also covered are the “repatriation” campaigns” of the Midwest during the Depression that deported both adults and children, 75 percent of whom were U.S.-born. Other stories include those of the garment, laundry, and cannery worker strikes, told from the perspective of Chicanas on the ground. From the women who fought and died in the Mexican Revolution to those marching with their young children today for immigrant rights, every story draws inspiration.”

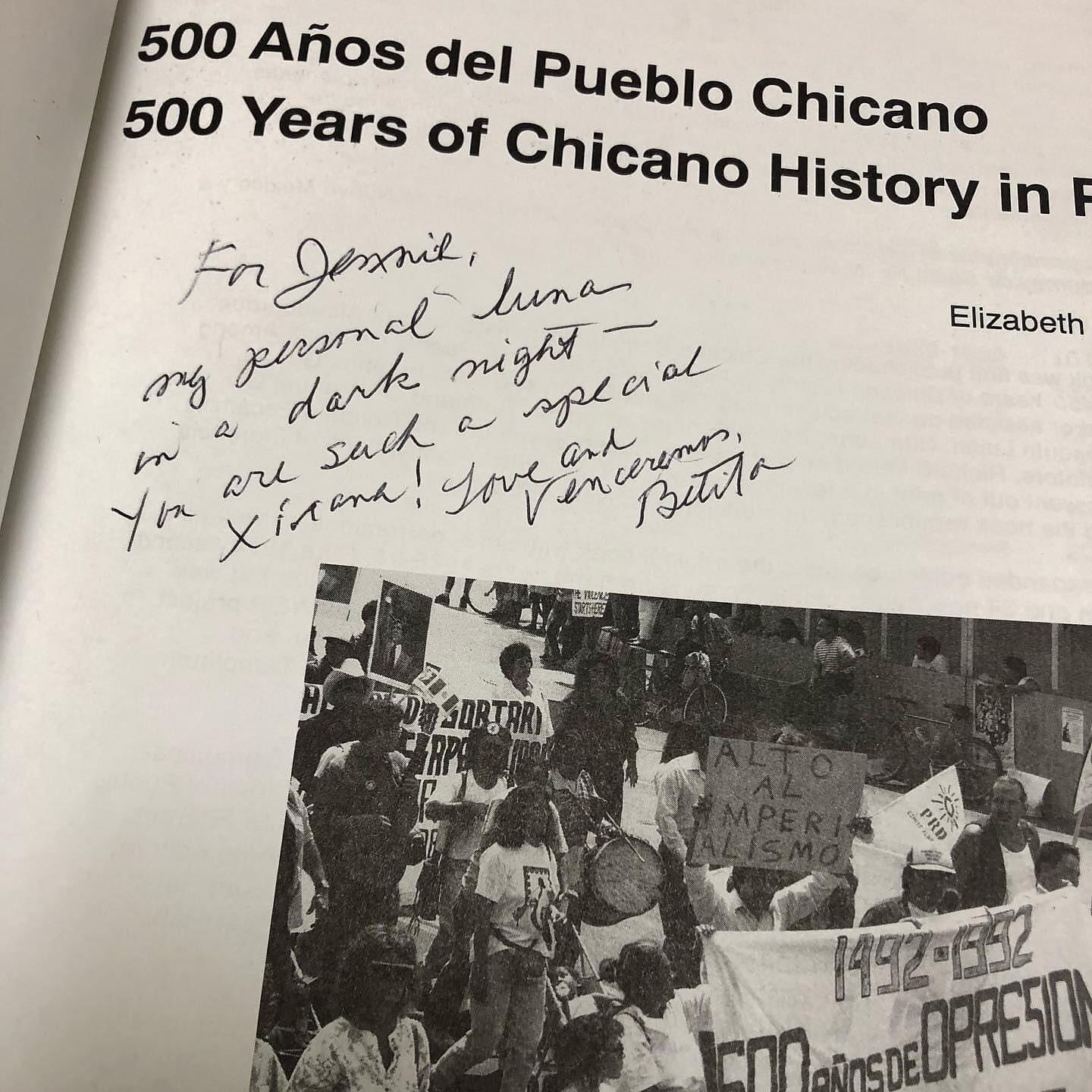

Jennie Luna, Favianna Rodriguez, Maylei Blackwell among many more participated in the creation of the book.

Jennie Luna shares, “My fondest memory is going to her home in San Francisco with her dog Xóchitl to drop off something we were working on for the book, and she said, ‘sit and have lunch with me.’ She made me a salad with goddess dressing and chicken, and I just remember feeling so touched, that here was an elder who was larger than life to me and she was preparing lunch for me. Her humility, grace, and kindness will stay with me forever. I cherish that afternoon where we sat and enjoyed each other’s company. I can still hear her voice say with such joy, ‘It’s Jennie Luna!'”