Activist and Mentor

Betita’s smile always shined bright in the streets. She came alive on the front lines of protests as did her contagious humor and joy.

Betita’s father taught her early on about the impact of U.S. imperialism on the people of Mexico. One of Betita’s first jobs after she graduated college in 1946 was working as a researcher for the recently formed United Nations. She traveled throughout Africa and the Pacific where she visited European and U.S. colonial territories and grew acquainted with the grave impact of colonialism.

That was also the time she began what would turn into a long life of global activism against racial and colonial exploitation. One of her first successful actions was to leak her report on the grim reality of life under colonialism to Third World U.N. delegates. The Philippines was the first to publicly announce the findings at a U.N. meeting in Geneva. This information gave occupied territories leverage to condemn colonial powers on the international stage.

Betita was an inspired internationalist who committed herself to protest and defy the tyranny of U.S. imperialism at every turn.

Jennie Luna, who received her PhD in Native American Studies at UC Davis in 2012 and is now Associate Professor of Chicana/o Studies at CSU Channel Islands, is one of the many scholars and activists Betita inspired. Jennie writes:

“I always felt inspired by her speeches and her presence, always wearing a beautiful huipil dress with pride. I am a better human for having known Betita.”

Betita was “my mentor, my role model and fierce warrior-activist, and most importantly, my dear friend.”

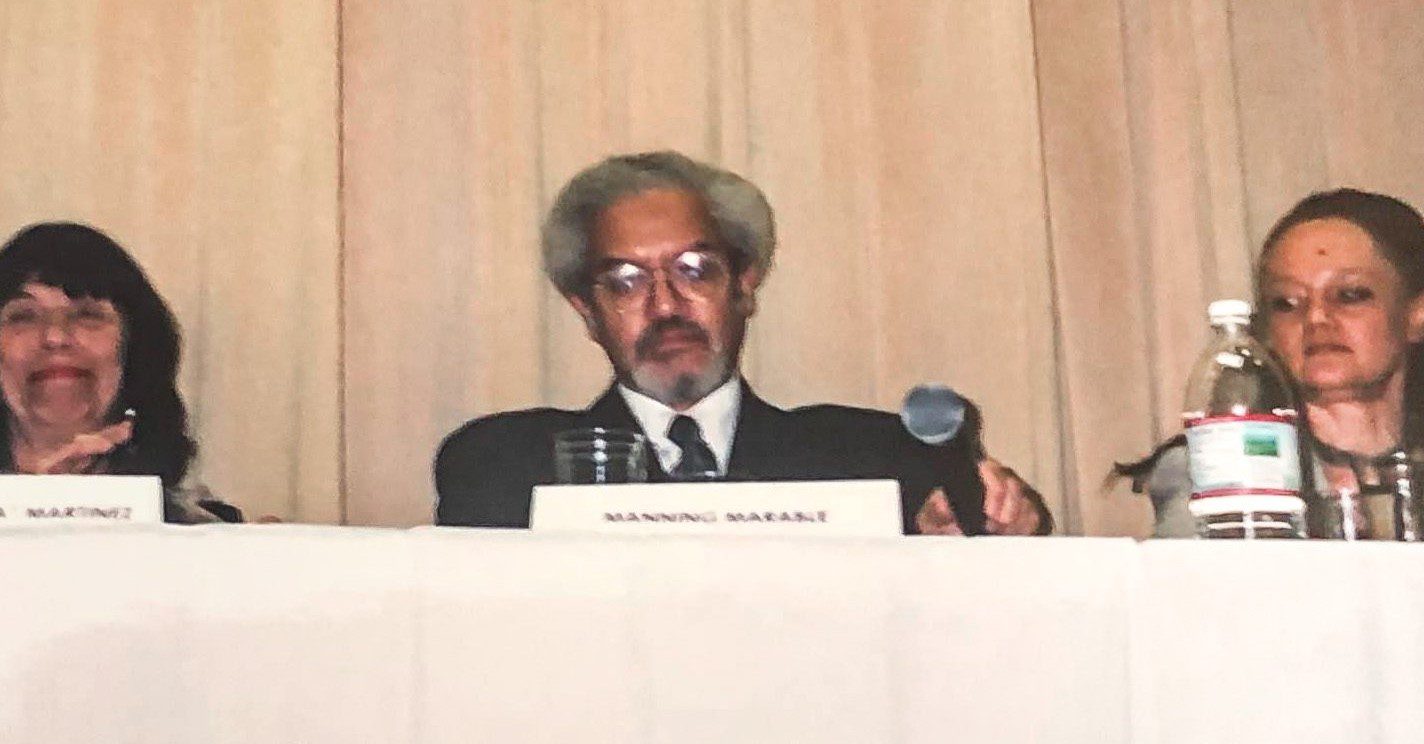

“Recently a student asked me if I had a favorite figure in the Chicano/a Movement and I responded immediately…Betita…she was a visionary committed to the goal of multiracial justice; she saw her life and work intricately linked to the struggles of others. My admiration, respect, love and gratitude for Betita runs deep… She came to the defense of MEChA at UC Berkeley. She encouraged me to write and helped me publish my first article in Z magazine. I could pick up the phone and ask her for advice on movement organizing. She brought me into her 500 years of Chicana History project to write and gather photos about Danza. She brought me into a panel on the New Chicano Left at NACCS where I was brought into a circle of incredible activist thinkers & intellectuals. I was often the youngest member in these invitations, but Betita never made me feel like I didn’t belong…on the contrary, her confidence in me helped me see in myself what she saw.

“I don’t think I fully understood at the time that she was cultivating the next generation of activist scholars. She would do these things because it was part of her feminist politic and ethic, expecting nothing in return. I often thought about how her contributions to Chicana liberation were rarely taught in the classroom and she was not given her place in history equally to her male counterparts, mostly because of patriarchy, but partially because she was just doing the work that needed to be done for the people and not for the sake of recognition. Whenever called upon to speak to youth, she was there.”

Building Cross-Racial Solidarity

Betita believed in building transnational struggles for freedom and decolonization and in strengthening solidarity among people of color around the world. In her twenties, Betita worked for the United Nations in various roles for six years researching the conditions of life in U.S. and European colonial territories in Africa, India and the Pacific.

In 1971, Betita wrote in El Grito del Norte, “we should learn about our sisters around the world, because someday we shall together form a force that nothing can stop.”

Thirty years later, as a board member for the Women of Color Resource Center, Betita helped organize its delegation to the World Conference Against Racism (WCAR), held in Durban, South Africa, on August 28, 2001.

When the United States seized half of Mexico by war in 1846, it launched a process of colonization that became the basis for deep-rooted, institutionalized racism. Mexican people in the Southwest U.S. have been lynched like African Americans in the South. The U.S. economy grew rapidly thanks to the cheap labor available from people of Mexican origin—a racist exploitation that continues today. This workshop will discuss the racism experienced by Mexican American people, which remains unknown to most of the world.

—World Conference Against Racism panel description written by Betita Martinez

Betita Martinez combined her life lessons on the frontlines of SNCC, the Freedom Summer, the Chicano, Chicana and feminist movements to birth the Institute for MultiRacial Justice. Along with fellow co-founders Phil Hutchings, Jason Ferreira and Elena Featherstone, here Betita pursued one of her callings and true life passions—building bridges among people of color. The Institute aimed “to strengthen the struggle against white supremacy by serving as a resource center to help build alliances among peoples of color.” In 2005, I had the honor of editing Betita’s essay, “Unite and Rebel! Challenges and Strategies in Building Alliances,” for publication in The Color of Violence: the INCITE! Anthology. Betita’s chapter shared several pressing lessons on building cross-racial solidarities, including the following: “dealing with our differences and divisions cannot be left to casual concern or spontaneous resolution. It has to be one of our organizational priorities, a clear-cut part of program.” (INCITE! p.192)

In one of Betita’s presentations at the Challenging White Supremacy Workshop in San Francisco, she defined the grim horrors of white supremacy while delivering a spirited call for transformation. In “What is White Supremacy?”, she defined it as “an historically based, institutionally perpetuated system of exploitation and oppression of continents, nations, and peoples of color by white peoples and nations of the European continent, for the purpose of maintaining and defending a system of wealth, power, and privilege.”