A Tale of Two Tastings

Get a glimpse behind the scenes of the Judgment of Paris, the 1976 blind tasting that put California wines on the global map, through items from two collections newly acquired by the UC Davis Library. The exhibit also sheds light on an earlier tasting in which a 1957 Hanzell Chardonnay bested a 1955 Corton-Charlemagne.

The Judgment of Paris

The Judgment of Paris, the 1976 blind tasting during which California wines scored higher than a selection of fine Burgundies, is widely known today as the event that put California wine on the map. The story of the tasting, written for Time Magazine by the sole reporter present, George Taber, was expanded into a book and later memorialized in the largely fictional movie Bottle Shock. For more than a century, American winemakers had been laboring to replicate Old World classics. The ’76 Paris tasting proved that wine made by “kids from the sticks” could meet the standards set by the elite tasters in the French wine world, and encouraged the ambitions of less recognized wine regions internationally. If Californians could do it, why not Chileans? Why not Australian and Chinese winemakers? The Judgment of Paris was the archetypal story of the underdog prevailing over a Goliath and strong evidence of what American ambition and ingenuity could do. But every story leaves out facts, and myths are often a faint outline of the true events they represent. Writers can play an important role in correcting the historical record, as wine writer Esther Mobley did in her articles for the San Francisco Chronicle, “The hidden figures behind the Judgment of Paris” and “How a Napa divorcee saved the Judgment of Paris.” A rchives also recover the lost details, shine new light on them, and retell timeworn stories with added texture and new relevance.

The Judgment of Paris stands out as an important event in the global history of food and wine. Its story, however, is far richer than Taber’s account or the sensationalized drama of Bottle Shock. As wine writer Hugh Johnson states in “California Wine: An International View,” “statistically overwhelming it may have been, but there is nothing surprising in the California wine-boom of the seventies.” The foundation for success had been laid by pioneering winemakers like Charles Wetmore, Ernest and Herman Wente and their father, Carl, Andre Tchelistcheff, Brad Webb, Louis M. and Louis P. Martini, Robert Mondavi, Fred McCrea, Lee Stewart, and many others.

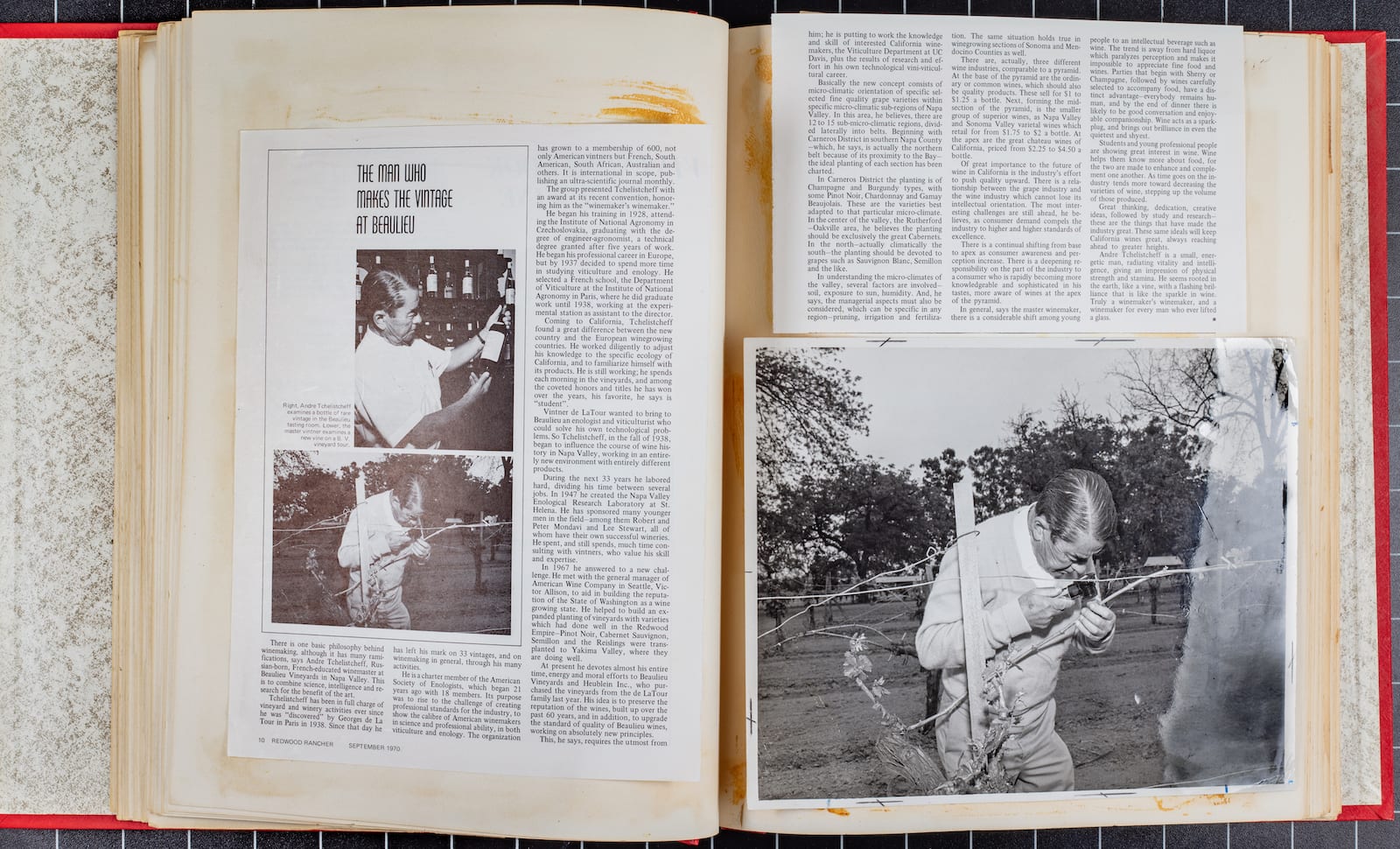

A spread from a scrapbook created by Dorothy Tchelistcheff documenting the career of her husband, winemaker André Tchelistcheff.

The UC Davis Library’s new exhibit, A Tale of Two Tastings, highlights some of the characters and encounters that marked the evolution of California wine recognized as “fine” or “premium”: a manuscript titled Gentlemen Vintners of California, written in the 1960s, mentions a blind tasting in Paris during which a 1957 Hanzell Chardonnay bested a 1955 Corton-Charlemagne. Letters discovered in wine writer Leon Adams’ archive, which was acquired by the library in 1990, describe that tasting in more detail.

The exhibit also highlights items from two related collections newly acquired by the library. Notably, the exhibit includes scrapbooks from the collection of Dorothy Tchelistcheff, the wife of André Tchelistcheff, California’s most influential winemaker after Prohibition. The exhibit also features documents and photographs from the collection of Joanne DePuy, founder of Wine Tours International, who coordinated the American vintners’ tour to Paris, led by Mr. Tchelistcheff, that coincided with the 1976 Paris tasting. It’s thanks to Ms. DePuy that the American wines made it to Paris.

Draft page from Gentlemen Vintners of California, by Frank Cameron, undated.

Ms. DePuy founded Wine Tours International because she wanted to “build a wine bridge between Napa Valley and other countries.” Tchelistcheff, a Russian-born winemaker who studied in France, was the perfect embodiment of that bridge. The Judgment of Paris further democratized wine making, and raised the personal bar for winemakers throughout the world. It was an important tasting — and more was at stake than anyone realized at the time — but it was facilitated by the free exchange of ideas and plant matter across political lines.