From Bean to Brand

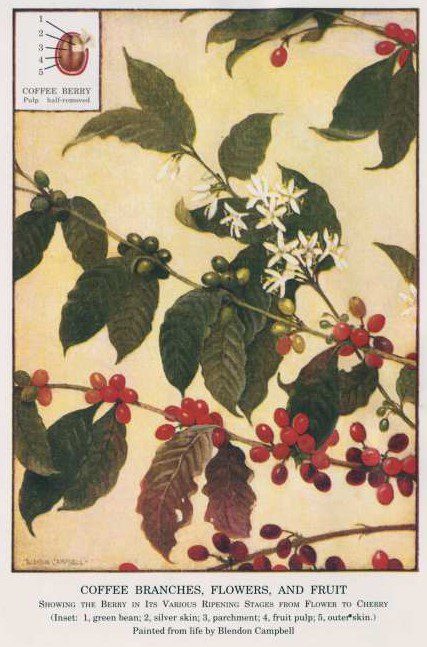

The coffee plant is a flowering shrub that grows under semi-shaded canopy. The seeds at the base of the flower develop into coffee “cherries,” which each contain two seeds or “beans.” Ripe coffee cherries are harvested either by selective hand-picking, stripping, or use of a mechanical harvester. Cherries are then processed to remove the layers surrounding the bean using either a “dry” method in the sun or a “wet” method, which uses substantial amounts of water. This processing is followed by resting for one or two months before milling to remove the remaining parchment, resulting in “green” coffee beans. Coffee roasters complete the work to ready the beans for sale.

Specialty Coffee Association Records, D-818

Only five to ten percent of coffee is sourced for “specialty coffee” – coffee that is identified by its geographic origin and distinct flavors that reflect where it’s grown, under what conditions, such as temperature, elevation, and shading, and how and when it’s processed.

Specialty Coffee Association Records, D-818

Wartime and Coffee

Specialty Coffee Association Records, D-818

Coffee and war have long been intertwined in United States history. In 1773, leading up to the Boston Tea Party and in the face of unreasonable taxation, coffee became the beverage of choice as a cheaper, patriotic alternative to British-controlled tea. After the American Revolution, coffee endured as the nation’s drink, remaining vital during future conflicts.

During the Civil War, coffee rations replaced those of alcohol in the Union army. The large rations (equivalent to 10 cups a day) gave these soldiers an edge in energy and morale over their Confederate counterparts, who had limited access to coffee because of the Union blockade of the Southern coast.

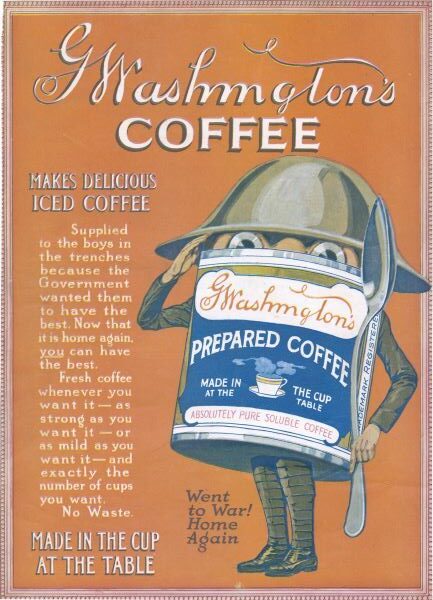

During World War I, coffee was hailed as important as bread in the trenches of Europe. Instant coffee, a new standard ration, created a convenient way for soldiers to enjoy a taste of home on the front lines, a practice that continued through World War II. During World War II, coffee emerged as a powerful symbol of American identity. Japan, fearing its opposing influence, banned the import, sale, and roasting of coffee, while in Italy, American soldiers mixed espresso with water to create the Americano as we still know it today, a lasting example of coffee and war’s combined past.

Coffee Brewing and Roasting

In the 18th century, coffee advocates urged consumers not to drink coffee that had been boiled directly in water, which resulted in a bitter brew. Many advocated for “drip” coffee, where boiling water was poured over finely-ground coffee packed in an upper chamber of a pot. The Rumford coffee pot popularized this method, which was described in more detail in Rumford’s essay, “Excellent Qualities of Coffee and the Art of Making it in the Highest Perfection” (1812).

In the United States, the Old Dominion coffee pot (patented in 1856 and widely distributed by 1859) functioned as an early percolator and refined how Americans brewed coffee. While advertisements claimed that the pot prevented the escape of aroma and flavor, the pot’s brewed coffee helped establish the thinner-bodied, bitter-tasting beverage still widely consumed.

In 1864, Jabez Burns invented a self-emptying coffee roaster that reduced roasting and grinding time, thereby lowering the price difference between green and roasted coffee in the marketplace. John Arbuckle bought a Burns roaster, which rapidly transformed his company’s sales of pre-roasted coffee in sealed paper bags.

Sir Benjamin Thompson, Graf von Rumford

“Of the excellent qualities of coffee, and the art of making it in the highest perfection” (1812)

First published in 1922, All About Coffee quickly established itself as a comprehensive, quintessential text offering guidance that still endures. Author William Ukers also served as editor for The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal, a longstanding industry publication at the heart of the burgeoning U.S. coffee industry, with offices located centrally among Wall Street coffee traders.

All About Coffee included information and illustrations about influential coffee inventions such as the insulated drip coffee pot designed by American scientist and inventor Benjamin Thompson, also known as Count Rumford, pictured here.